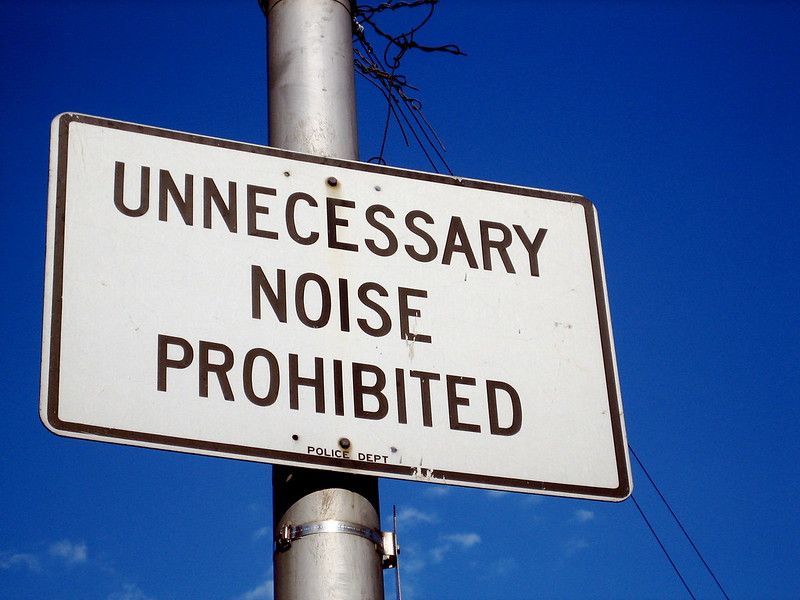

What can you actually do about car alarm noise in New York City?

The city almost fully banned car alarms 20 years ago, but they're still everywhere today.

In 2002, Aaron Friedman was in the middle of one of his regular eight-hour stretches at the piano in his Washington Heights apartment when his concentration was ripped apart by the hardest-to-ignore of New York City annoyances: the car alarm.

It’s a situation every resident of every neighborhood in the city knows well: parked cars across the street from Friedman’s apartment were raging against a phantom thief every time a heavy truck went by, blaring their circus of noises to no one in particular, their owners nowhere in sight on heaven or earth. That day the alarms repeated about every 10 minutes.

“This is not a crime situation, this is just a huge nuisance,” he told The Groove, a statement that distills the entire problem with car alarms in the city for the past three decades.

Stats show the alarms are ineffective at stopping any car thefts, but pretty damn effective at ruining a night’s sleep for anyone who happens to be on the block. The malfunctioning personal private property of one person becomes the pain of hundreds. All the unremarkable clatter that a car alarm causes can lead to pretty good conditions to steal a car, some criminologists say.

That nuisance 22 years ago sent Friedman from average grad student down a path of civic activism that had him tussling with car manufacturers and lobbying the city — and it culminated in the effort that was the closest the city ever came to banning car alarms outright. He and other activists were able to get the City Council to pass a law to ban installation of certain types of alarms in the city; far from a total victory, but, he thought at the time, a good start.

“I felt like that was a nice try, I was glad that people took it seriously,” said Friedman, who kept up his musical ambitions despite those interruptions at the piano: he founded Make Music New York in 2006 and now runs its national operation. “I was skeptical that anything would change.”

In the decades since, no other major attempt to address car alarm nuisance noise en masse ever gained any ground. If you judge by the amount of people who claim to be single-issue voters on this topic, this seems like a winning issue for any politician, but nothing much has happened.

There are certain annoyances of city life that are immovable facts of life, and that you even can find endearing with time — the bus schedules, the slow walkers, music at all hours of the night. But there are some that are just the relics of petulant personal behavior that we should not accept as par for the course, things that stand in the way of us having a more sane, slightly less aggravating city. Car alarm noise is one of those; so is honking. Most of them are car-related, come to think of it.

So what are you actually supposed to do if there’s a nuisance alarm going off in your neighborhood for hours, and you haven’t quite got the energy to steal the car yourself just to drive it somewhere farther away? When the expletive-laden note just doesn’t hit the spot, you have a few options:

What you’re supposed to do about a car alarm

First up we must as always give the good-citizen and good-neighbor disclaimer: as with any conflict in the city, talking directly to the person responsible for the problem is usually the best bet before you escalate things. That said, this is often impossible when a car alarm is going off. The car might be far away, hidden on the maze of blocks and half blocks of your neighborhood; almost certainly, the owner is far away, leaving their car to whoop and holler all night far from their own home, where they are presumably sleeping in a bed of hell flames, as they deserve.

Instinct tells you to call 311 but, no. Because an alarm is meant to, at least in theory, indicate a crime in progress, 311 will transfer you directly to 911. That dispatcher will ask you for as much info as possible about the vehicle: make, model, color, location and plate number. You give them as much info as you can.

What counts as an illegal alarm?

The city lays this out very specifically in its noise code. A car alarm is only supposed to be activated by “direct physical contact” with the car, or through clicking a button on the key fob. That means all the car alarms on your street that start raving whenever someone with a large speaker or big truck passes them by are illegal. The alarms are supposed to shut off after three minutes. Anything longer than that and it’s fair game, and you can snitch on it.

What happens after that is what happens after anytime you call 911 and ask the NYPD to do something: sometimes they do something, and sometimes they don’t!

OK but what are they supposed to do?

Like most crimes in progress, they’re supposed to stop it. The city code says the NYPD “shall have the right to take such steps as may be reasonable and necessary to disconnect any audible burglar alarm … that is installed on a motor vehicle at any time during the period of its activation.” Various sources online say this can mean disabling the alarm in some way, or, more likely, towing the car. The car owner is responsible for the towing fee.

City code also says owners of cars with alarms are actually supposed to register the alarm with the local precinct, and then leave the phone number of that precinct on display in the car so someone can contact the owner in the case of an errant alarm. Not reckoning that one happens that often.

What actually happens when you do this?

I can tell you from experience. Like many folks, I avoid calling 911 unless I am certain there is someone in danger, mostly because many things going on in public are largely 1) not my business 2) unlikely to be improved by the presence of a police officer or 3) may sound like the largest brawl in the history of fists, but turn out to be something normal like two teens talking after school, in the boisterous way that teens do. I’ve called 911 four times in my city life, once for someone literally running up and down my street at night shouting for help — which still could have been a teen in action, I don’t know — and three other times for a car alarm. One of those times I thought someone might be genuinely in distress and trapped in a car, trying to signal for help, but in the other cases, the alarm was just relentless in a way that felt like a theft of time and sanity from my whole block, so I called 911.

One of these times was a few weeks ago: I finally caught sight of a van that had been belching sounds all night long at about 10 minute intervals, echoing off the brick buildings of my block. About 15 minutes after I called, a police cruiser rolled up my street, parked illegally at the intersection, and two officers emerged to inspect the vehicle. They then walked down the street, returning about 10 minutes later, got in their illegally parked car and drove away.

I had to leave the apartment at this point so whether they towed the van or not, I never found out, but it was gone that night one way or the other. (The NYPD did not respond to requests for comment about how this process is supposed to work).

What happened to trying to ban car alarms?

They were banned, kind of. Anti-alarm activists really raised the, uh, alarm in the early aughts about the issue, and were able to galvanize a broad coalition against car alarms. Friedman and others successfully got a bill in front of the City Council that would ban third-party car alarms, the ones installed after the car leaves the factory. The bill passed the Council, but Mayor Michael Bloomberg vetoed it, saying it wasn’t fair because it didn’t target all car alarms, while also saying it would be a gift to car thieves. But the Council overrode that veto, giving us the regulations listed above.

That said, people clearly still have car alarms. Auto shops around the city advertise installing them, and anyone can cross the line into New Jersey or Long Island to get one. But car manufacturers have stopped installing them as much; new technology makes cars nearly impossible to steal without the right key fob on hand.

I checked in with a few workers who probably deal with more alarms than the rest of us — parking garage attendants — to see if they had any tricks for disabling them. One told me it’s the older, aftermarket alarms that act up mostly, becoming more sensitive to vibrations and other things over time. But if attendants don’t have the car’s keys or the owner’s contact information, they can’t do anything about it.

“No, you just have to live with it,” one Manhattan attendant told me while chuckling.

Instead of feeling dispirited to still be dealing with this issue 20 years later, Friedman told me he actually found the experience a good lesson in what happens when you don’t accept the status quo.

“I came into this whole project literally as, like, a totally man-on-the-street kind of person,” he said. “I had no political background, training, connections.”

It wasn’t a total win, but he felt like he spoke up and helped make a difference.

“Politics can actually work out,” he said.

Can I just lift the car like this scene in Twins?

Sadly, despite all your pedestrian dreams of Hulking out on a wailing automobile, this doesn’t actually work to disable an alarm. If that were the case, no car alarms would work on a hill. Still if you want to lift a car and move it somewhere to show your disapproval of the alarm, that’s pretty funny to me.

Can I devote my life to becoming a vigilante who breaks into cars and turns off their alarms like Tim Robbins in Noise?

Sadly, also no.

Comments ()