American Santa is a Native New Yorker and don't you forget it

It’s no secret that New York City was founded by immigrants. 400 years later migrants are still arriving in New York by the busload — sometimes welcomed, sometimes weaponized — becoming part of the fabric of the city.

But what many people may not realize is that New York City immigrants aren’t just responsible for the birth of the city we know and love — they’re also the driving force behind most of the modern idea of Christmas. The holiday wasn’t born here, obviously, but the internationally celebrated, commercialized version (public trees, holiday lights, holiday markets, mall Santas) traces back to New York. Specifically, they go back to immigrants landing here and doing what immigrants always do: keeping pieces of home alive. Immigrants built the holiday by bringing winter rituals from home that made sense in the worst of winter.

And then New York, being the center of the planet, beamed them out to the rest of the world. Below, a brief, festive history of Christmas traditions that came straight from our city’s immigrants over the centuries:

Sinterklaas, rooftops, stockings and more

The Dutch were the first to shape New York into a commerce-obsessed port city. Henry Hudson’s arrival brought Dutch settlers in the late 1600s, and with them came both the foundations of a money-making colony and a set of winter traditions that a native New Yorker would then disseminate out into broader American culture.

American Santa, in other words, is a native New Yorker.

Washington Irving (1783–1859) was America’s first literary celebrity, the country’s inaugural “professional writer” at a time when that wasn’t really a job. A New Yorker born to English and Scottish immigrant parents, he grew up in Manhattan absorbing the city’s history, which he later satirized and mythologized in works like A History of New York under the Dutch persona “Diedrich Knickerbocker.” Irving had a gift for remixing European traditions into warm, distinctly American stories; his The Sketch Book (1819–20) is what introduced the world to The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and also revived old English Christmas customs. Though A Christmas Carol gets a lot of credit for defining Christmas, Dickens owes a debt to the sentimental, cozy holiday world Irving crafted decades earlier. Irving is the hinge point where New York immigrant culture becomes American culture, and where Christmas shifts from winter chaos into the domestic, emotional holiday we now celebrate.

Irving borrowed European Christmas customs and reframed them as rituals of family, warmth and social harmony; values he believed were foundational to a young America. Many of the images we now consider “classic” Christmas (gift giving, saint day treats, stockings by the fire) were originally Dutch. And Irving showed Americans how to see them.

In A History of New York (1809), Irving goes beyond parodies of the city’s origin story through Dutch folklore. One of his stories describes a Dutch scouting party shipwrecked on Manhattan, where a member receives a vision of “good St. Nicholas” riding over the treetops in the same wagon he uses to deliver yearly gifts to children. In the vision, St. Nick instructs the Dutch to settle on the island. In Irving’s telling, Saint Nicholas himself becomes the founding father of New York. American Santa, in other words, is a native New Yorker. Irving lifts old tales of Sinterklaas and folds them into the scene: a rooftop riding, chimney slipping Dutch saint tied directly to Manhattan’s origin story. It’s satire, and the first draft of American Santa.

And the Christmas tree market continues the Dutch tradition of identity through commerce. Germans brought the tree itself (more on that later), but a Dutchman named Mark Carr invented the sidewalk version. In the early 1800s, to get a Christmas tree, New Yorkers had to go outside the city and lug it back. In 1851 Carr decided to bring back a whole wagon of evergreens to sell to city dwellers. His wife laughed; he sold out on the first day.

The New York Christmas tree lot, arguably one of the best-smelling things in the city, especially mixed with roasted nuts, was born. Another immigrant ritual, amplified by New York.

Trees, lights, holiday markets

German immigrants didn’t just add to New York’s Christmas, they defined the aesthetic, giving us trees, lights and holiday markets. By the mid-1800s, New York had one of the largest German populations in the world, especially on the Lower East Side, and those families brought winter rituals that blended pagan light traditions, Christian symbolism, and old world nostalgia. New York took what they missed from home and amplified it all into the look and feel of American Christmas.

German New Yorkers were the ones who revived evergreen culture in the city. In Europe, the Christmas tree traces back to Yule rituals: pagans using evergreen branches as symbols of life in the dead of winter, candles warding off spirits, and “light in the darkness” ceremonies marking the solstice. Early Christians in Germany absorbed those pre-Christian rituals, pairing trees with nativity symbolism, and by the 19th century, German immigrants were bringing the merged tradition straight into New York.

Then there are the holiday markets, now in some of the city's busiest areas and extremely competitive to get in, but originally with roots in medieval Germany. New York’s holiday markets are modeled on Christkindlmarkets, literally “Christ Child Markets.” Since the 1300s, these markets filled town squares with open-air stalls selling food, drink, ornaments, candles, textiles, and seasonal treats, usually accompanied by singing and dancing. During the Industrial Revolution, German immigrants (and plenty of other Americans) longed for that simpler, pre-industrial feeling and revived folk markets in the United States as an antidote to skyscrapers, steam engines and factory work.

But the modern Christmas market was unintentionally shaped by a very dark chapter German history. In the 1930s, the Nazi regime tried to strip Christmas of its Christian associations and remake it as an Aryan nationalist holiday. They leaned into Germany’s pagan past, pushing “Germanic” rituals and mandating that markets sell secular, folkloric wares: ornaments, toys, gingerbread, festive displays and atmospheric lights meant to echo advent candles. Organizers leaned hard into garlands, glass balls and fairy lights, the same visual language that defines holiday markets today. Food stalls soon began selling bratwurst and other German treats, which remain staples almost a century later.

It’s a complicated legacy, but those developments turned markets from simple mercantile events into immersive, experiential winter villages, the aspiring vibe at places like Bryant Park and Union Square today. And in a nod to their roots, you can still find Glühwein (warm, spiced mulled wine pronounced "GLEE VINE") at most of New York’s markets each December, alongside the textiles, ornaments, candles, and food that trace directly back to centuries of German winter tradition.

Wassail, yule logs and cozy domesticity

Before the Dutch and Germans shaped New York’s Christmas, the English shaped the early American colonies themselves, bringing with them centuries of winter folklore and rowdy seasonal customs. By the 1700s, English influence defined much of American cultural life, even as the colonies and the crown drifted toward war. But after the Revolution, anything “too English” suddenly felt suspect; traditional Christmas celebrations were dismissed as foreign, undignified, or downright un-American. Some religious communities even banned Christmas entirely because of its association with drunken revelry and street brawling (the original Santacon?). The holiday needed a rebrand, which came through literature.

Washington Irving steps back in. In The Sketch Book (1819–20): he borrowed old English winter customs and wrapped them in cozy domestic fantasy. He imagined games like Snap Dragon and Bob Apple, wassail bowls with roasted apples floating on top, pheasant pies decorated with peacock feathers, candles glowing in windows, and carolers wandering the countryside.

Irving takes these practices (many originally designed to ward off bad spirits during the darkest stretch of the year) and reframes them as rituals of communal joy. His “Old Christmas” tales imagine a nostalgic trip to the English countryside to revive these rituals, and readers embrace the vision wholeheartedly. He positions Christmas not as a public bacchanal but as a soft, heartwarming season essential to American nation building. Dickens reads Irving, absorbs that cozy domestic mood, and writes A Christmas Carol, a story that cements the emotional register of Christmas for the entire English-speaking world.

Many of the traditions we now consider “classic Christmas” (mistletoe, evergreen boughs, festive feasts, holiday greetings, carolers at the door) come to American consciousness through the English. The English give Christmas its emotional warmth while Dutch and Germans supply the visuals and sensory world. New York stitches it all together.

By the mid-1800s, New York had gathered a blend of winter traditions brought over by immigrants trying to keep pieces of home alive. The city then combined them, amplified them and sent them out into the world. As the center of publishing, advertising, department stores, art, mass media, public space and spectacle, New York is the cultural megaphone that made Christmas an American holiday.

This is New York functioning as publishing capital: taking immigrant folklore and turning it into a national character.

Christmas: the New York City remix

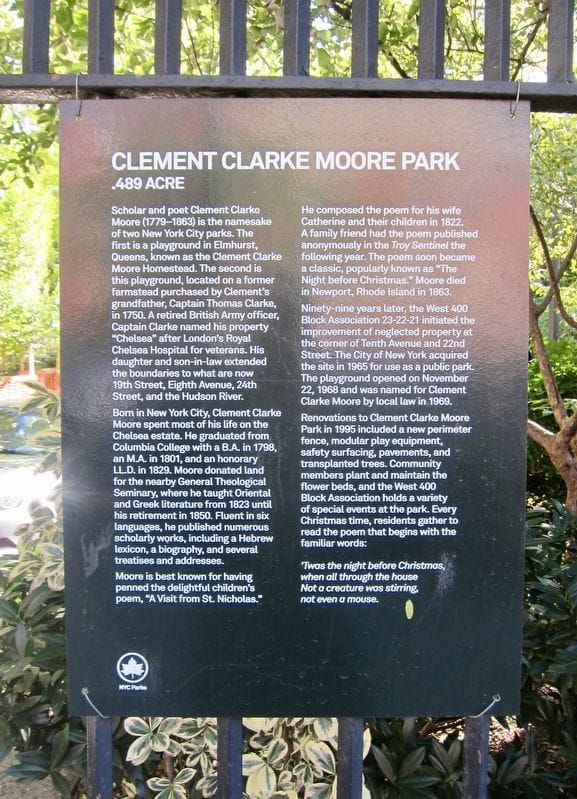

Once New York had absorbed Dutch, German and English winter traditions, the city rewrote the story. Take Santa Claus: Irving gave him the treetop wagon and the Dutch satire; Clement Clarke Moore, writing from Chelsea in 1823, added the chimney descent, the choreography and the eight reindeer with their now famous names. Then Thomas Nast at Harper’s Weekly completed the image in 1862, drawing the full-bodied Santa: fat, jolly, fur-trimmed, generous and surrounded by a workshop of German elf folklore. This is New York functioning as publishing capital: taking immigrant folklore and turning it into a national character.

With the characters and traditions were all established, New York City as media and commercial juggernaut kicked things into higher gear:

Windows, trees, street theater

Once literature shaped Santa, New York’s department stores shaped everything else. Cheap plate glass from the Industrial Revolution made massive windows possible for the first time, and 1870s Manhattan (an emerging fashion capital) ran with it. Retailers packed entire districts with dressmakers, milliners, and import shops, then used oversized windows to turn browsing into window shopping. Margaret Getchell, Macy’s first woman executive (and marketing genius), transformed displays into street side theater, including dressing live cats in doll clothes and staging scenes from famous novels like Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

By the early 1900s, the holiday season had become retail’s main event. November and December delivered a quarter of annual sales, prompting stores to pour money into elaborate displays. Depression-era windows became free entertainment for New Yorkers who couldn’t afford theater tickets. Lord & Taylor unveiled animated scenes using electric motors; Salvador Dalí smashed the Bonwit Teller window after they altered his surrealist display. Today, holiday windows require yearlong planning, a 200-person team, and draw tens of thousands of people daily. New York made Christmas public, theatrical, and leaned into its capitalism.

Trees for everyone

In 1912, Madison Square Park debuted the first public Christmas tree in the United States: a 60-foot Norway spruce lit with 2,300 colored bulbs sent by Edison himself. The tradition was started by Emilie D. Lee Herreshoff to allow all New Yorkers to enjoy the holiday spectacle, attracting 25,000 visitors to the first ceremony. Families who couldn’t afford their own trees gathered there by the thousands; within a year, more than 50 American cities copied the idea.

From that moment on, New York democratized Christmas, turning private rituals into shared urban experiences. In 1931 a group of construction workers pooled money together to buy a tree in the pit that was originally Rockefeller Center. This original tree was only 20 feet, with "strings of cranberries, garlands of paper, and even a few tin cans" on Christmas Eve. With the lighting of the 50-foot-tall first official tree in 1933, this caught on and became popularized as a way for the public to celebrate.

Rockefeller, media and movies

Part of Rockefeller Center’s image makeover as a holiday destination started during the Great Depression. After that original tree in 1931, the tradition became an official part of Rockefeller Center's celebrations by 1933. The skating rink followed in 1936; WWII blackout trees in the 1940s; LED eras, with solar panels and 900-pound Swarovski stars arriving later on. In 1951, NBC broadcast the tree lighting, officially transforming New York into winter’s national stage.

Hollywood did the rest. Miracle on 34th Street (starring an immigrant in the lead role of Santa), Home Alone 2, Elf — decade after decade, filmmakers return to New York because the city already looks like the holiday: lights, windows, trees, spectacle. New York broadcasts its immigrant-built version of Christmas until the whole world begins to recognize this Christmas as the Christmas we all know.

Comments ()