Winter used to be a reprieve from high ConEd bills, but not any more

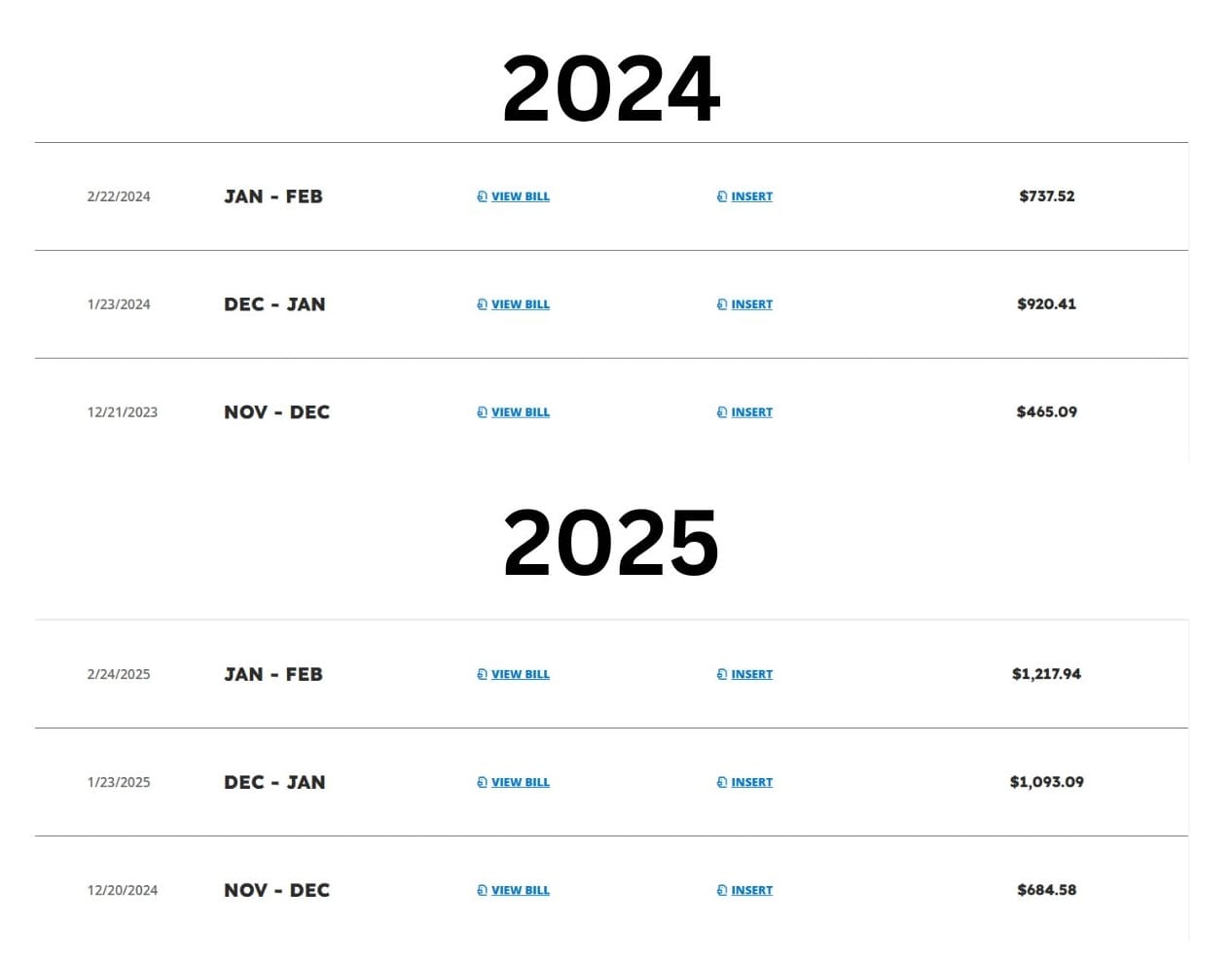

New Yorkers have been raising a ruckus in group chats and ever-growing neighborhood Reddit posts over the past few months, saying that their ConEd bills have seemingly skyrocketed, sometimes by hundreds of dollars, from previous bills or compared to last winter. Bills from a handful of New Yorkers around the city I reviewed show jumps of up to $500 for this winter compared to last year.

"It’s been a nightmare," one Brooklyn resident told The Groove of her recent $800 bill.

“It’s been a topic on my building WhatsApp,” grumbled one Prospect Heights homeowner.

Another Brooklyn renter wrote on Reddit in January: “We’ve been keeping the heaters off since we know how high Con Edison bills can get during the winter. But this month’s bill is absolutely insane, way higher than anything we’ve ever seen.”

Another Williamsburg resident, who said their bill went from $300 last year to $500 this winter, complained on Reddit: “My room is all windows. It's freezing but I try to only use the heat at night. How does this happen? Do I need to just keep it off and bundle up?”

People expect their bill to jump during the summer, when appliances work harder and inefficient air conditioning units run all day, and the winter price surge is causing a bit of shock. In some parts of the city, ConEd provides both gas and electric, but in others (like Brooklyn) it provides electric only.

But is ConEd, an essential and only-game-in-town utility which New Yorkers have no choice but to patronize, causing the problems? ConEd says the uptick in charges is not their fault, and some activists actually agree.

“The best way to manage your cost is to manage your usage,” ConEd spokesman Allan Drury told The Groove. The utility says it hears from customers (and journalists) every year around this time, complaining about skyrocketing utility bills in the winter. But when it assesses those bills, it finds surges in usage hours account for the increase.

Running the numbers

A few bills I examined did show recent bills had more usage hours than last year’s statements.

One resident of a multi-unit apartment building in Bed-Stuy shared her bill that showed her charges went from $228 one month last winter to $400 this February. The bill also showed she used about double the electricity in the 2025 billing period. What caused the spike in usage, however, was still a mystery.

“Honestly, no clue. I have wall mounted AC units and haven’t changed how I use them virtually at all,” she said, “so I’m not sure why the number fully doubled.”

Another bill I saw, from Andrew in Crown Heights, showed an increase of almost $500 from February of last year to February of this year. The bill showed he used about 1,200 more kilowatt hours of electricity this year than last too. He said this winter’s cold snaps, compared to mild winters in recent years, may be the culprit.

“My guess is that this was primarily due to the weather, the bulk of electricity usage is for heating,” he said. “Any seal around a door or window is very drafty as well.”

So how are those bills actually calculated?

The problem with blaming ConEd alone is that they actually don’t make any money on the energy they supply your home with. Instead, the energy the company buys on the wholesale market is sold without profit or loss by the company to the consumer. It declares on its website “What we pay, you pay.”

“Con Edison is kinda like this middle man between us and all those energy companies,” said Stylianos Karolidis, an energy activist with the Democratic Socialists of America who worked on the group’s successful bid to pass the Build Public Renewables Act in 2023.

The utility does make money on other costs, like delivery charges, which cover infrastructure and the cost of bringing energy to your home. But those are state-regulated, and more or less fixed from bill to bill (on the above Bed-Stuy resident’s bill, the delivery charges were actually lower than in 2024).

“When you see month-to-month changes in your bill, besides usage, the biggest factor will be how much Con Edison is paying for that electricity,” Karolidis said. “It gets really really expensive in winter months.”

Understanding exactly why ConEd itself is paying so much for the energy is complicated, and involves tracing North American natural gas markets, inflation rates, disruptions to pipeline service, extreme weather events — and now, chaotic games of tariff chicken that our president is playing with Canada.

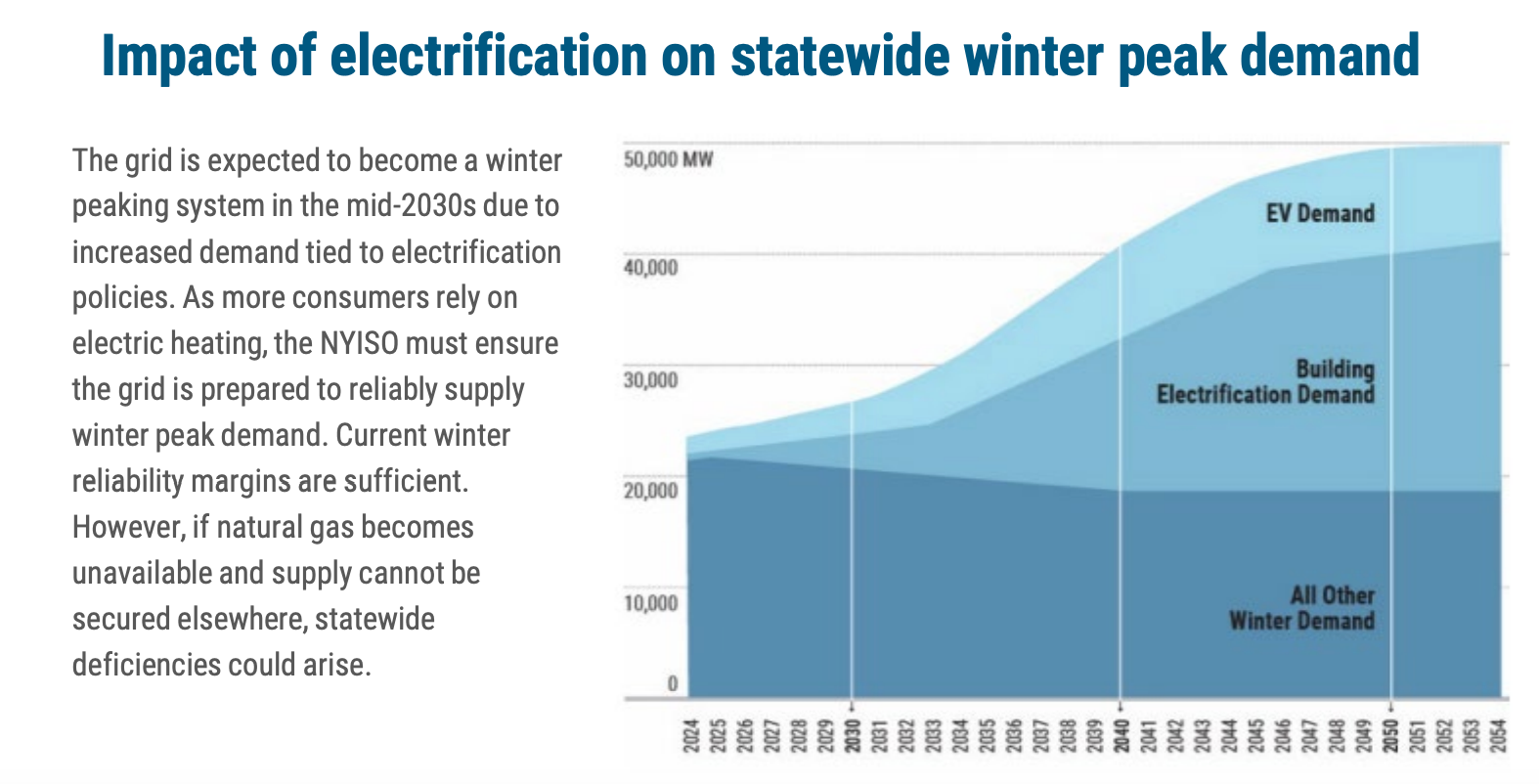

But we’re also entering what experts call a “winter-peaking grid” of energy; instead of the highest energy costs landing in the summer, due to air conditioners, fridges and the like, costs will be higher in the winter, thanks to electrified buildings, electric vehicle usage and electric heating systems. Higher demand nationwide means higher prices for everyone.

Karolidis doesn’t let ConEd off the hook entirely — he noted the utility is seeking state approval for controversial delivery rate increases next year, and their monopoly of the system is part of the problem. But he said not every rate change is under their control.

“It’s not like ConEd is the one that’s arbitrarily raising prices,” he said. “This is a whole system-wide problem that comes from reliance on fossil fuels.”

In fact, the demand is only likely to increase: in 2020, about 13 percent of New Yorkers in the state heated their homes with electric heat, according to a report by the New York state Assembly. That number is expected to move toward 100 percent as the state nears its goal to majorly cut greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.

This whiplash as the city and state shift away from fossil-fuel-burning furnaces toward plugged-in eclectic systems might be part of the sticker shock on recent bills. The rush to electrify buildings will take some adjustment — especially since the electric grid still pulls a lot of its energy from fossil fuels (more on this later).

“Holy shit. Just moved into a fully electric building and almost shit myself on the first bill,” said Travis, a Bed-Stuy resident who recently relocated to a brownstone that was built in 1901 and gut renovated in 2022. His bill for February came to $802 for 2,100 hours of energy.

“My electric bill for my previous building on the hottest or coldest months was $180 and that was running an A/C all day or a heatstorm.”

Now, bills for his unit are more expensive but “never actually warm. All my plants died within a week of moving.”

Courtney, who also lives in Bed-Stuy, said her old brownstone apartment with radiator heat averaged heating bills of $100 a month; she moved to a different brownstone advertising “energy efficient” air conditioning and heat units; her most recent bill was $802.

Other price complaints seem to have more mundane answers: One Redditor in Long Island City complained about a $500 heating bill this winter, before realizing that they left a window open for two weeks while traveling.

“Taking my L but it still sucks,” they wrote in an update on the post.

Another Reddit user responded with a "FUCK MY LIFE" when others pointed out that running space heaters 24 hours a day, instead of their in-building electric heating, was probably the reason for their $1,000 bill.

ConEd said it worked with customers to provide more than $300 million in energy assistance for low-income residents last year.

"We are acutely aware of the affordability challenge,” Drury said via email. “We are committed to enrolling as many eligible customers into our program and will continue advocating for policies that make utility bills more affordable.”

Customers who are in arrears on payments can sign up for a payment plan so they can pay the debt down over time.

What you can do about it

New Yorkers don’t really have a choice when it comes to electricity providers, so the answers to what you can do about your high energy bill include the practical: don’t use space heaters, unplug “vampire appliances” like TVs, modems and our ever-proliferating collection of screen-having, noise-making smart devices that suck energy even when you’re not home. But some tips are less practical, especially for a renter, like replacing your old fridge.

Con Ed itself offers money-saving guidance, including offering free energy-saving products for multifamily buildings (such as LED light bulbs) and installing a smart thermostat, which lets ConEd remotely make adjustments to your thermostat when demand is high.

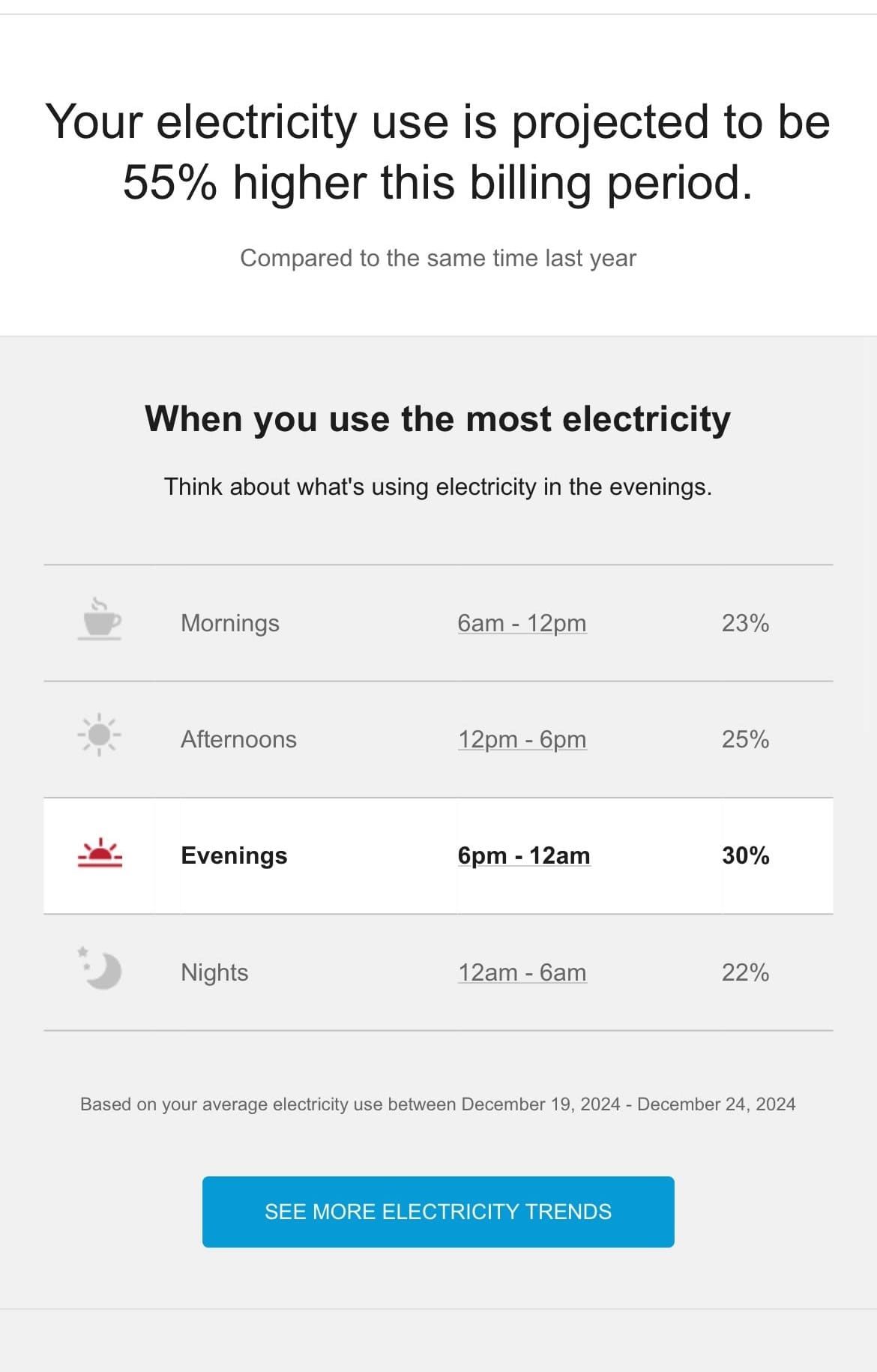

Other tips they suggest call for cleaning your heating ducts frequently and considering hand-drying dishes from your dishwasher. Customers who have a smart meter can see real-time energy usage on the utility’s website as well, to see when surges in energy use are happening in the home.

One homeowner in Ocean Hill showed me her monitoring history that said most of her energy use that led to a higher bill was coming between the hours of 6pm and midnight, but she wasn’t sure what to do with that information.

The bigger solution, as Karolidis and many climate activists across the city have been fighting for, is to divorce our city’s energy grid from fossil fuels entirely.

“If we want consistent prices, we have to move to sustainable energy,” he said.

There’s good news on that front: Karolidis and other activists were successful in their efforts to get the state to pass the aforementioned Build Public Renewables Act in 2023. It directs the New York Power Authority to plan, build and operate renewable energy projects to meet the state’s renewable energy goals. It would also replace polluting gas plants that kick into action during peak energy demand periods with renewable energy plants. It will take time for the state to build out those facilities, but activists hope it will lead to energy being less of a capitalist commodity.

“Imagine if we derived the vast majority of our energy from a renewable source: Solar, wind, hydropower,” he said. “There’s no additional cost to additional supply. That would simply exist. Supply charges would be substantially lower.”

For now, he said anyone upset about their bills should keep an eye on publicpowerny.org, which tracks the build public renewables effort and progress.

ConEd doesn’t control all the rates, but it still makes plenty of money for its investors, with $15 billion in profit in 2024.

“There’s no reason whatsoever we should live in a city where we’re forced to pay a private company hundreds of dollars any month so they can make a higher profit,” he said of ConEd. “All of that money instead should go back into the system.”

Even if ConEd is not solely responsible for the current bill complaints, they’re still a middleman, one whose costs could hopefully be eliminated in a greener future.

“Think about your water: publicly managed, it’s great,” he said. “People in New York love the water system. Energy could be like that.”

💸 If you found this useful, become a member to support our work, or send us a one-time donation.

Comments ()