Everything to know about City of Yes if you haven’t been paying attention

The mayor's signature policy plan is up for a major vote today — here's your crib sheet if you're just catching up on the whole thing now.

If you haven’t locked in on what City of Yes is or why it’s so important — what, you’ve been overwhelmed and busy keeping track of other political news? — today is the day to learn.

A would-be policy cornerstone of the Adams administration, City of Yes has the potential to create thousands of badly-needed new housing units every year, mainly through slashing assorted red tape that tends to stand in the way of their construction. It could mean freeing up space to build apartments over one-story commercial buildings and converting some of the city’s many under-utilized office buildings into housing. Hey, then if you work from home you’ll technically be in the office still, take that, boss.

Interestingly, the plan has also united Mayor Adams and many of his frequent enemies including progressive members of City Council, and created political maneuvering that’s only gotten more potent as the mayor faces an avalanche of legal problems — more on that later.

Like so many things standing in the way of progress in this city, the whole thing might come down to parking. A big part of the plan calls for eliminating parking mandates in new construction. Every parking space increases the cost of a building between $50,000 to $100,000, meaning everything gets more expensive and fewer apartments get built. But — you will never believe this — some people in this city will never give up parking, and that might tank or significantly reduce the impact of the whole plan. Maybe we can all buy cars to live in for free on the street!

In any case, the whole thing has the potential to be a seismic shift in how things get done in the city, and has also come with plenty of political drama attached. Ahead of a major City of Yes City Council vote later today, consider this your crib sheet to catch up on this rare, important piece of Eric Adams news that isn’t yet another indictment or raid:

Remind me what this even is — what are we supposed to be saying “Yes” to?

Eric Adams first laid the groundwork for “City of Yes” back in 2022, outlining a plan that’s broken into three main proposals focused on “carbon neutrality,” “economic opportunity” and “housing opportunity.” The topline idea of the whole thing is to clear up red tape that stands in the way of common-good development, whether that be for improving the carbon footprint of buildings, converting the usage of buildings, or just creating more buildings period, among other things.

“We are going to turn New York into a ‘City of Yes’ — yes in my backyard, yes on my block, yes in my neighborhood,” Mayor Adams said in the initial presser. “New Yorkers are not going to wait around while other cities and other countries sprint towards a post-pandemic world, and now we won’t have to.”

The climate portion, which was designed to pave the way for more green tech like solar panels, wind turbines and electric vehicle charging, passed a City Council vote last December.

The economic opportunity portion, which passed in June, included provisions to increase green manufacturing space, allow thousands of businesses in industrial areas to expand, and the removal of the last vestiges “cabaret law” restrictions on dancing in bars and restaurants, to name a few.

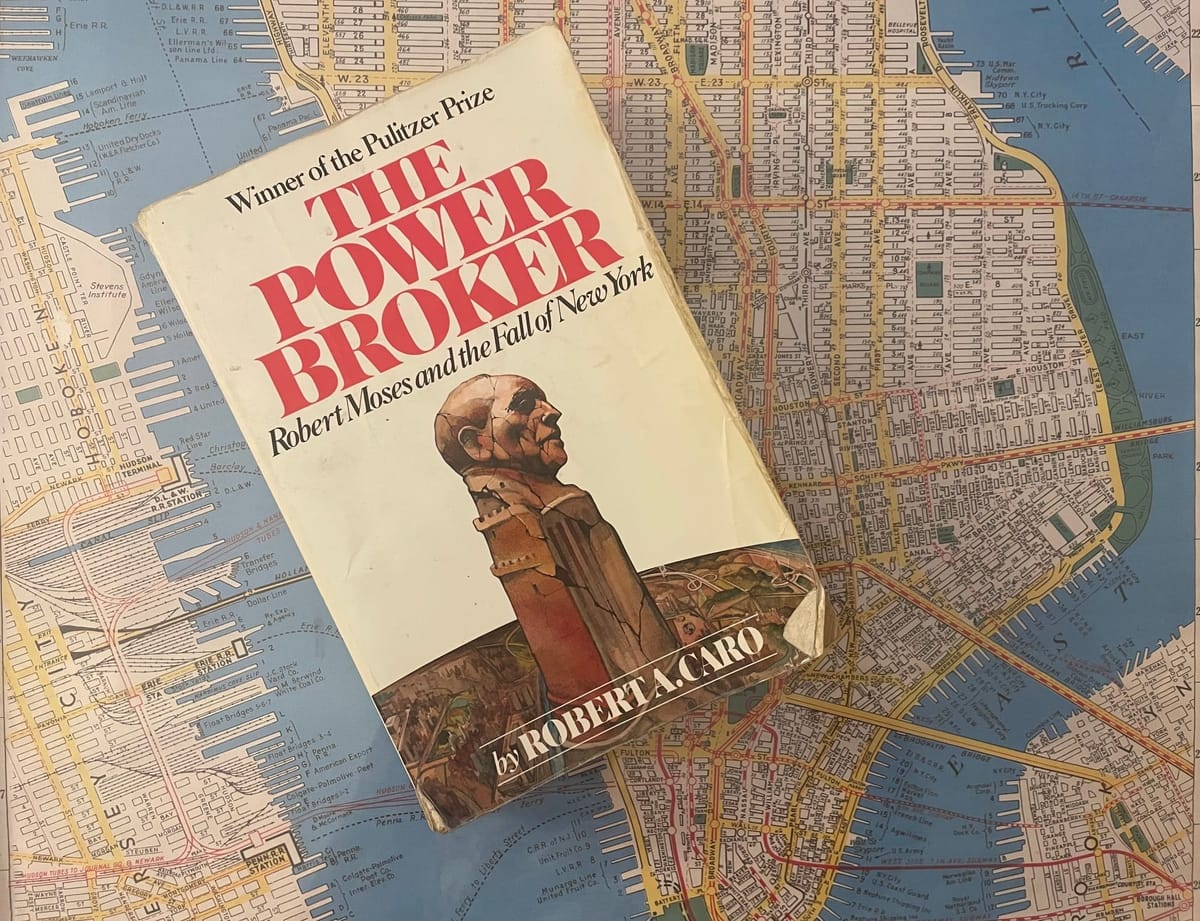

(A note on the absurd-sounding concept of “cabaret laws”: dancing in bars in New York City was illegal until very recently. In 2017, the city finally repealed the Cabaret Law, a prohibition era relic that was occasionally used to raid places in a very Footloose-y way right up until its repeal. Dancing was illegal in New York City until 2017 should give you the same feeling when you say “constructing an apartment building without a parking garage was illegal until 2024.” The parking mandates were another gem from Robert Moses, who loved cars so much he should have married one, and advocates say it’s time to undo another piece of this guy’s legacy for good.)

Today’s voting focuses on the third and probably most controversial portion of City of Yes; the one that deals with housing.

In its ideal form, the plan is designed to create more than 100,000 new housing units over the next 15 years. Marquee parts of the plan include:

- An end to onerous parking requirements for new housing developments.

- Allowing for the use of “accessory dwelling units” like basement apartments and backyard structures (the likes of which have been a linchpin of housing efforts in other parts of the country, notably in West Coast cities).

- The creation of housing units above businesses on some commercial streets.

- Creation and approval of new housing near transit stops.

We’ll get into these in more detail shortly.

How actually bad has the housing problem gotten?

Bad enough that even 100,000 new units would be the tip of the iceberg in solving this thing. (But still a good start, to be clear.)

In its current state, the City of Yes plan is projected to create between 4,000 and 7,000 new housing units per year through 2039, on top of the roughly 20,000 to 29,000 units already being created annually. Adams has said that the city needs to add 50,000 housing units per year over the coming decade, meaning that even in the best case scenario, new housing under this plan won’t keep up with demand.

With its focus on deregulation in service of new construction, City of Yes also does little to address the ongoing affordability crisis, unless you’re of the school of thought that new development automatically has a trickle-down effect of lowering or at least slowing the growth of rents across the market. (The TL;DR on that is that while new housing stock is an essential piece of the puzzle here, talk to anyone who lives near some of the new towers in, say, Williamsburg or Greenpoint, and we doubt you’ll hear many stories about their rents going down. It’s complicated.)

That sounds big, what kind of projects would be affected?

It’s a lot of things that fall under the umbrella of “oh god where can we fit more housing?” Here’s a rundown of the biggest ticket items:

Denser, taller, faster, stronger

The City of Yes plan allows for buildings to be taller, so long as a portion of the units are set aside for permanent affordable housing.

Developers would be able to build 20% more units in their buildings so long as they use those units for affordable housing; “affordable” is always relative to the neighborhood but this new plan would restrict those units to people earning 60% of the median income of the area. Currently, people making 80% of the area median income can qualify for units like this.

You can’t park there

The city currently mandates that every new construction, from the gleaming glass towers to the smaller new-construction condos looming over your neighborhood (often unfairly maligned as the “gentrification building”) have new parking. That’s the case even if it’s right next to a train station, even in the city with the most sprawling public transit system, even in a world where we simply must stop burning dinosaur bones to go grocery shopping.

City of Yes would eliminate this mandate, for the goal of reducing construction costs and creating more room for apartments. Each parking space adds between $50,000 to $100,000 to building construction costs. And you thought the brokers’ fees were the problem! It’s also an induced demand thing: if you build parking spaces, cars will come, and then that gentrification building will be full of people who drive themselves to work every morning instead of sweating it out on the subway with their neighbors.

Building near train stations and over one-story pizzerias

The first question everyone in the history of New York City has ever asked when looking for an apartment is “what train is it near?” The idea in this plan is a simple one: to encourage the building of dense units near train stations. This is mostly targeted at the outer borough neighborhoods where single-family homes take up much of the space now, and those kinds of developments are not allowed. And many of those folks are opposed to changing that because an apartment building is offensive to their sense of the character of the neighborhood. The same goes for commercial strip zoning in a lot of those areas: the city is full of streets where apartments are stacked on top of commercial businesses like laundromats and pizza shops; but that kind of development is illegal in many areas. Instead you get a row of one-story businesses that has a very New Jersey suburbs vibe (derogatory).

The problem is, we can’t put all the new housing units we need in Lower Manhattan, so some neighborhoods are going to have to accept the terrifying concept that not everyone wants or needs to live in a whole ass house.

It’s cool to live in the garage

As we touched on above, the expansion of Accessory Dwelling Units as potential housing has been a big part of affordable housing initiatives in other parts of the country, albeit ones where it’s more common to have things like “a backyard” with “room for any kind of structure in it.”

The ADUs provision in City of Yes would allow homeowners to rent out “backyard cottages” and “garage conversions” as residences, yes, but crucially, it also includes the legalization of basement apartments, something housing advocates have spent years pushing for.

The Office: An American Living Place

Many people have spent the work-from-home years looking at all the tall empty office buildings in the city and thinking: why can’t they turn them into housing? The answer is: zoning, and the answer to that zoning problem is potentially City of Yes.

OK, so besides Eric Adams, who’s in favor of this?

An unusually broad coalition, actually — this is a rare case where you’ve got the Real Estate Board of New York, urban planners and affordable housing advocates largely on the same side, though they may disagree on some of the specifics. The picture has grown more complicated amid Adams’ spiraling legal woes — it’s a prime opportunity to use his political weakness as leverage to get whatever it is one might want for one’s district — and as Gothamist reported earlier this fall, Councilmembers in the Progressive Caucus, who are usually opposed to Adams on just about everything, may be key to getting this deal across the finish line.

Who hates it?

You might have guessed it: the people who live in the most suburban parts of the city are against the de-suburbanization parts of this plan. This map lays it out pretty clearly: Community Boards in the garage-friendly neighborhoods on the outer edge of the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens, and all of Staten Island, voted against the plan.

So what’s next next/what’s the thing happening today?

As we mentioned earlier, today’s the day for two key City Council committees to vote on this thing starting at 11 a.m. As of right now at let's see here, almost 10 a.m. there's still no deal, so what kind of compromises and provisions will be carved out is still an open question. After that, it will go for full Council approval next month.

The question of eliminating parking minimums is still being heavily haggled over, and will likely be watered down in order to appease lawmakers from the aforementioned garage-friendly neighborhoods, per reporting on Streetsblog. (Think the street parking equivalent of the whole congestion pricing neutering that just happened.)

But all that said, New Yorkers might end today with new legislation in the works to make at least minor inroads in the never-ending war against both cars and the housing crisis. That, and a rare Adams-related news cycle that has absolutely nothing to do with his alleged numerous crimes.

Update 11/22/24:

As expected, a modified version of City of Yes was approved in yesterday’s City Council committee votes, albeit with some last-minute changes.

To get the deal across the finish line, the Adams administration agreed to keep in place mandatory parking space minimums for buildings in lower-density areas, a key concession to the car-loving sickos who were raising some of the loudest opposition to the plan. Some restrictions to Accessory Dwelling Units have also been added, and the size of some “transit-oriented development districts” near LIRR stations has been decreased.

The Mayor also agreed to allocate $5 billion in city and state funding for staffing at housing agencies along with projects including sewers, streets and open spaces.

In a statement praising the final iteration of City of Yes for Housing Opportunity as a major win, Rachel Fee, executive director of the New York Housing Conference, also said, “This is really the best version we are going to get.” If that’s not politics, we don’t know what is.

Comments ()