How to unionize your pizza shop

Barboncino set the blueprint for a union wave in New York City's restaurant world

By Virginia K. Smith

It started with a basement full of sewage water and floating tampons. Never what you want at a restaurant.

“[In June 2021] there was a pretty extreme workplace safety incident,” said Aidan Hart, a member of the organizing committee at Barboncino, the Franklin Avenue institution that made headlines last month as the first New York City pizzeria to unionize.

“A pipe burst downstairs, near where all the clean [dishes] are stored, where all our dough is stored, where the walk-in fridge is,” he said. “I was busing with another one of our organizing committee members that night, and we spent the next two hours basically voiding sewage water, getting covered in it, dripping wet.”

“There were literally toiletry products, pieces of toilet paper, menstrual products floating around,” added Alex Dinndorf, a server and organizing committee member at Barboncino, which has been dishing out Neapolitan-style wood-fired pizzas, small plates and cocktails to Crown Heights locals since 2011.

With 90 minutes left of the evening’s dinner service, Hart said, the restaurant’s then-owner gave instructions over the phone: any workers who’d finished cleaning up the basement needed to get back on the floor. Go back to busing tables and serving customers, sewage-drenched clothes and all.

“That was when we actually started organizing in earnest,” Hart told The Groove.

Since news first broke of Barboncino workers’ unanimous vote in favor of forming a union, other workers in the city’s famously brutal service industry have taken notice, and made moves to form union shops of their own.

“We’ve got folks in an organizing capacity now that represent in total about 300 restaurant workers in Brooklyn,” said Richard A. Minter, vice president and director organizing for Workers United, the union that represents the Barboncino workers. (Workers United was also behind the campaign to organize Starbucks.)

Earlier this week, workers at the Downtown Brooklyn location of Alamo Drafthouse petitioned the National Labor Relations Board for an election to join a local of United Auto Workers.

“It’s all underground committee building, capacity building, getting to a point of coverage here where we feel we can begin to go public on some of these,” Minter said. “And Barboncino are the leaders of that movement.”

So how did the industry get to this point, and what lessons can workers at other shops crib from the Barboncino team’s win? Let’s get into it:

A tough nut to crack

Time was, none of this would have been particularly remarkable: for much of the 20th century, the vast majority of the restaurant industry was unionized. So much so that in the 1960s, New York City’s powerful union of bagel makers managed to go toe-to-toe with the mob to stop an attempted takeover, per Grub Street.

But like so many other branches of organized labor, things started to go downhill for hospitality unions in the 1980s. Large chain restaurants and non-union shops started to gain an ever-increasing share of the market, and netted enticingly high profit margins for their owners. At the high point, nearly a quarter of restaurant workers belonged to a union, according to Slate. In 2022, just 1.4% of food service industry workers were members of unions, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Even amid the cross-industry groundswell of organizing that’s grabbed headlines in the past few years, the restaurant sector has been a tough nut to crack.

“There’s a number of factors that play into the space,” Minter told us. “Turnover among workers is extremely high, it’s often a transient position. Factors like that, low pay, and at times immigration issues, makes it tough to organize.”

At the start of 2023, the staff at upscale Rockefeller Center eatery Lodi made moves to organize with the Restaurant Workers Union, but ultimately voted not to unionize. That election has since been contested amid allegations of illegal union-busting tactics from management. (The union is currently awaiting results of an investigation from the National Labor Relations Board, a representative told us.)

So how did Barboncino pull it off?

After the night of the burst pipe, it was time for action. It was time for…forms.

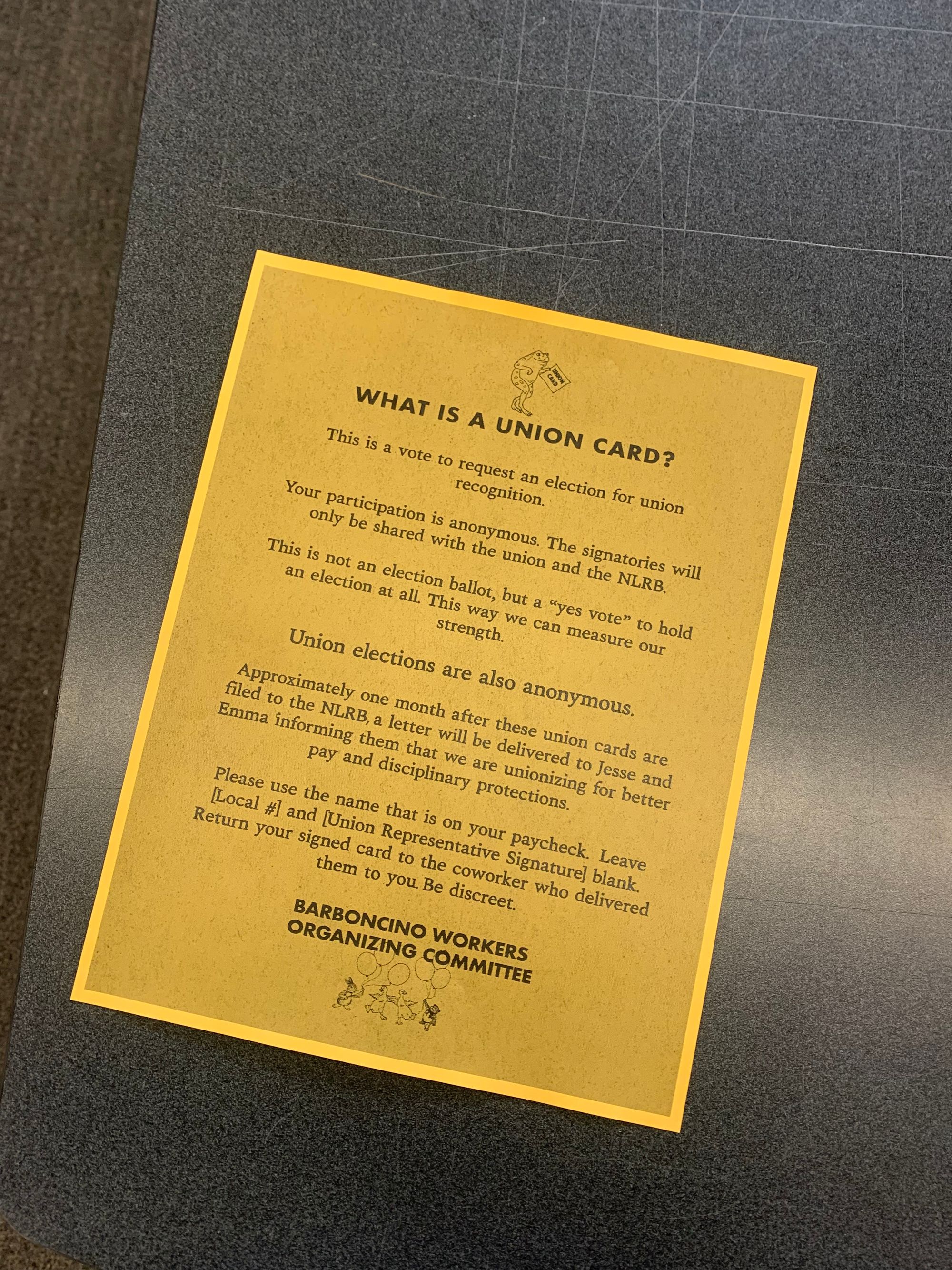

A Barboncino comrade filled out an intake form outlining the basic details of the situation for the Emergency Workplace Organizing Committee, a partnership between the Democratic Socialists of America and United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America that helps connects union-curious workers with organizers to help them figure out next steps. (A representative from EWOC declined to comment for this story.)

The team began working with an EWOC staff organizer who had previously worked with E-ZPass and Verizon workers.

“Our first objectives were just having organizing conversations, you know, someone would go out for a cigarette break and you would follow them,” Dinndorf said.

“I was amazed at how quickly people responded. Conventionally with unions you get rights like shop stewards and Weingarten rights,” Dinndorf added. “That was so unbelievably popular immediately. Everyone, especially in the back of the house, was so used to working in a place where you can get fired like that.”

Increased leverage for improved health and safety conditions was a major selling point for prospective union members, as well. “I think [the burst pipe] is a really dramatic example of something that happens in the service all the time,” Dinndorf said. “Like the only people who keep the actual guests safe are the workers.”

At the heart of any workplace issue, of course, is salary.

“If you work in a restaurant or any sector of the service industry in America, you and every single person you work with is not making enough money,” Hart said. “And every single one of you is going to agree on that. Focus on that, because it’s true, and it’s going to knit you together.”

Pay disparities are particularly potent in the Seamless and DoorDash age, when restaurants have seen an exponential increase in delivery demand — and in turn, output demand on their kitchens — without necessarily passing along those extra profits to their employees.

“They’ve quadrupled their sales because of deliveries, but that doesn’t translate to higher wages for anybody involved in making those sales,” said Becca Young, a Barboncino server and a member of the organizing committee. “At least as a server, when the restaurant is busy, we make more money because of tips. With deliveries, that money goes to Jesse [Shappell, current co-owner] and that money goes to the restaurant. It certainly doesn’t go to the kitchen that’s making four times the amount of pizzas they used to make.”

(The restaurant’s current owners, Shappell and Emma Walton, purchased Barboncino from previous management in October 2022. “It's our understanding that the organization effort was underway before we took over ownership,” Walton said in an emailed statement. “Now that the election has passed, we are currently reviewing the next steps of the process.”)

The Barboncino team’s EWOC organizer eventually connected them with Workers United, though workers can contact the union directly as well.

“We stand ready to support and implement our model,” Minter said. “We’re ready to take on those challenges and help workers. We believe workers need unions and we’re poised to stand in that space and help them through the process to get a better work experience through collective bargaining.”

(The Restaurant Workers Union is also open and enthusiastic to outreach from prospective shops, a representative told us via email.)

The next step for the Barboncino team is bargaining a formal contract, but even without one, unionization has already come with tangible benefits.

“Three weeks into the creation of our union, we’ve won things like additional training shifts for workers who need retraining, and cleaned the disciplinary slates of workers,” Dinndorf said.

The sometimes thorny work of organizing has felt well worth it not just for their own restaurant, but as an important step for the industry at large, union members say.

“None of this was even remotely unique to Barboncino. What is the point of either quitting or losing this job, then going to another restaurant and having the exact same thing or worse happening,” Hart said. “That was a lot of the calculus. Why leave? In many ways this is the best restaurant job most of us have had. We unionized because we love the place.”

Comments ()