Why isn’t there a legal weed shop in Brooklyn yet?

NYC’s legal weed market hits another roadblock as surplus languishes in freezers.

Marijuana has been legal in New York for almost two years, but not a single state-licensed dispensary has yet to open in Brooklyn. The lack of legal weed in one of the state’s most weed-hungry places highlights the series of nagging legal obstacles that have dogged the legal rollout, which Empire State cannabis boosters hope will be hashed out soon. But on Tuesday, litigation again delayed (legal) weed retail’s arrival in Kings County and elsewhere: an upstate judge said 30 retailers licensed under the state’s temporary regulations cannot move forward and open after all.

The state has issued 463 dispensary or delivery service licenses through its social-equity program, but less than two dozen are open. The soonest new stores could open is now October, state officials have said.

The shortage of retail locations has forced New York’s weed farmers to freeze their crops, giving some of their products an expiration date.

“We have all this biomass sitting in farms across the state, and no one is going to buy it because there’s no place to sell it,” state Sen. Jeremy Cooney, chair of the subcommittee on cannabis, told The Groove. “If the biomass is going into an edible product, you’re not going to taste any difference. If you’re putting it into a pre-roll, you will. They’re losing the ability to sell a lot of this product.”

Pot legalization in New York has been messy and confusing. Weed became legal to possess before it could be sold, and retail dispensaries barely trickled open as thousands of illicit stores popped up across the city. As of writing, there are just 23 licensed cannabis retailers open in New York state including five stores in Manhattan, one store in the Bronx and two delivery services based in the Bronx and Queens. And yes, none in Brooklyn.

Those businesses, and hundreds others approved for “Conditional Adult Use Recreational Dispensary” licenses, will likely have to wait until the state launches a permanent, non-”conditional” license process, which the Office of Cannabis Management has said should happen in October, barring more complications.

The rollout and legal troubles are frustrating and disappointing for many in the industry, but what does it all matter to you, the weed consumer? Let’s answer some burning questions about New York legal weed so you can achieve your optimal Empire State of consciousness.

Why aren’t there more legal stores?

New York’s weed law passed in 2021 with the goal to prioritize “communities disproportionately impacted” by marijuana prohibition (specifically, entrepreneurs with previous cannabis convictions), and tasked the Office of Cannabis Management to create rules to that end. Giving priority to some businesses over others has unsurprisingly led to lawsuits that have, to the fury of nearly everyone involved, hobbled the legalization rollout.

“The regulator created things that were susceptible to challenge and the challenges seem to be doing pretty well,” said Jeffrey Hoffman, an attorney who helps New York cannabis businesses get off the ground.

Right now, OCM is dealing with a suit from veterans who believe they should have been prioritized in the first batch of licenses. The state “marihuana” law specifically required officials “prioritize consideration” for applicants impacted by marijuana prohibition — as well as distressed farmers, women- and minority-owned businesses and veterans.

The law goes a bit further for disproportionately impacted communities by requiring OCM and the Cannabis Control Board "actively promote” their participation. But Albany County Supreme Court Judge Kevin Bryant has repeatedly ruled against the state after saying veterans didn’t get a fair shot at the licenses, freezing the status of the vast majority of those 400-plus licensees — and potentially putting existing licenses in legal jeopardy too.

On Tuesday, Bryant ruled that OCM had misrepresented the status of 30 licensees he’d previously said could proceed because they were “ready to open their dispensaries now,” saying that several of the companies were not, in fact, ready to launch. All 30 of those would-be stores — including six in Manhattan, five in Queens, one in the Bronx and one in Brooklyn — are back in limbo.

With the conditional program on the skids, industry advocates want OCM to open up applications to the general public. Cannabis board members are expected to vote on proposed regs at their Sept. 12 meeting, setting up OCM to launch its application the following month (you can submit a comment to that meeting here).

It’s unclear how long applicants would then have to wait to get approved and finally open, or if yet-to-open dispensaries licensed under the “conditional” regulations would even be first in line.

That means that for residents of Brooklyn and Queens, New York’s two biggest counties, questionable, illegal, ubiquitous bodega weed will remain the most convenient option, for now.

Wait, there are illegal weed stores?

Yes, most of the many, many weed storefronts you see in this beautiful city in 2023 are illegal operations, much to the chagrin of the entrepreneurs and advocates trying to build the legal market.

“Most consumers think wherever they’re shopping now is a legal store,” bemoaned Hoffman.

The illegal market — easily located in stores advertising “exotics” or “zaza” or often something less subtle — is a natural outgrowth of the state’s inability to meet demand so far in the legal market. That comes down to a lack of retail stores, not a lack of product. New York’s Cannabis Control Board and Office of Cannabis Management have yet to settle on an application process for wannabe shop-owners among the general public.

"If they make $30,000 or $40,000 a day, they don’t care if they get shut down because they made a bunch of money in a week.”

The few stores that have opened were able to do so on with the “conditional” license offered to charity-backed outfits or “justice-involved individuals” with previous marijuana convictions, Cooney said.

Even that has been hazy thanks to legal challenges along with a delayed roll out of $200 million in state dollars to help former convicts start businesses.

With so few stores open, the illicit market has thrived.

Illegal weed stores should be distinguished from your years-old delivery service, Cooney said. Legacy farmers and “dealers” with sophisticated operations have been preparing for years to enter the legal market, but the state has yet to provide them a legal path to do so.

“The legacy market were very sophisticated underground operations with clients, employees and lots of processes,” he said. “Illicit [shops] are these very quick pop-up stores there to make a buck. If they make $30,000 or $40,000 a day, they don’t care if they get shut down because they made a bunch of money in a week.”

The omnipresence of illicit shops has confused people across the state, said Cooney, whose Rochester district has plenty of pot bodegas but not one legal dispensary.

OK, the weed store on my block is not a legal dispensary, I get it. Why should I care?

We at The Groove are not in the business of telling anyone what to smoke or not smoke. A trusted dealer or delivery service of many years is not the same as a fly-by-night operation selling God knows what. Hoffman, the cannabis lawyer, said he can’t blame some New Yorkers for choosing the cheaper, more widespread option.

“The prices are lower, and some of the stuff is straight out of California, high-grade,” he said. “The consumer is not going to have legal options quickly enough, so they’re going to keep doing what they’re doing. You have to have a regulated market at all if you want to even attempt stopping the illicit market.”

Telling people what or what not to smoke may be a sticky business, but there are serious concerns about the quality and safety of bodega weed. There’s no guarantee of truth in packaging with unregulated products — and none of the extensive mold and pesticide testing required for cannabis sold on the legal market. To be blunt: A Times investigation last year found high levels of “E. coli, salmonella, nickel and lead” in flower, edibles and vapes from 20 different illicit shops.

On the legal market, “you’re paying for quality and you’re paying for safety,” explained Sasha Nutgent, the retail manager at Housing Works Cannabis Co. in the East Village, the state’s first licensed weed store.

“If there's something wrong with the product or if it’s not smoking the way you like it, hold on to your receipt, you're able to exchange and return with us,” Nutgent said. "With the bud man, I’m not sure that’s going to happen.” (Housing Works has a 30-day return policy.)

Are legal prices high?

The cheapest eighths of an ounce on a recent Tuesday at Housing Works — all from the brand TEAL — cost $25 at Housing Works, before an additional 13 percent tax. Other eighths can cost well over $60 after taxes on the legal market.

The prices on the illicit market are going to be much lower on average, either from your dealer or a legal storefront.

The higher price point could be considered the price of good civics: OCM-licensed weed shops and cultivators pay taxes, they pay their workers and, in some cases, donate their proceeds to charity. One hundred percent of Housing Works Cannabis Co.’s profits go back to Housing Works proper, which provides services to unhoused people with HIV and AIDS. Union Square Travel Agency on 13th Street is part-owned by the Doe Fund. Gotham, a shop on Bowery, is 51% owned by STRIVE, a workforce center in Harlem, which gets 51% of its profits. The actual products, meanwhile, are all grown and processed in New York by New York farmers and businesses.

“I don't think that [New Yorkers] really want an indica to slow them down.”

Alright, I’m willing to give legal weed a try. What should I buy?

A full list of New York’s legal cannabis sellers can be found here.

Around 70% of sales at Housing Works comes from sativa strains, at least in part because they are harder to find on the illicit market, Nutgent said. Customers seem to prefer sativa’s energizing high to the sleepier effects of indica and hybrid.

“It’s our culture of being a New Yorker, we’re on the go. We’re always looking for what’s next,” she said. “I don't think that people really want an indica to slow them down.”

The store’s “budtenders” are there to help you make sense of a constantly changing line of products. Weed is seasonal: some strains may be in good supply for one season, then off the market the next once the crop runs out.

“The brands are still the same, the farm is still the same, but the strains are different depending on the season,” Nutgent explained. “Each week we add about two or three new brands and vendors, so the menu will always change.”

“Flower,” the state’s legal term for smokable cannabis, is the top seller followed by vapes, edibles, pre-rolls, tinctures, concentrates and, in “dead last,” CBD, Nutgent said.

At Gotham on Bowery, founder and CEO Joanne Wilson is taking a slightly different approach. She told The Groove that the story charting “the future of retail,” where cannabis is only the background “concept” to move other goods. Thirty percent of the store’s profits so far have come from merchandise, Wilson said.

“We had a major comedian come in yesterday and buy $500 worth of merch, we were super excited. We're seeing celebrities come through,” Wilson said. “We're seeing athletes come through.”

Gotham is in the process of adding a delivery option, Wilson said. Housing Works, meanwhile, currently delivers to parts of Manhattan, north Brooklyn and western Queens, but plans to expand that delivery zone in as soon as a few weeks, Nutgent said.

One other category of store is also set to enter the market later this year: qualifying companies already licensed to sell medical cannabis in the state will be able open one recreational store each on Dec. 29 — exactly one year after Housing Works opened as the state’s first legal shop.

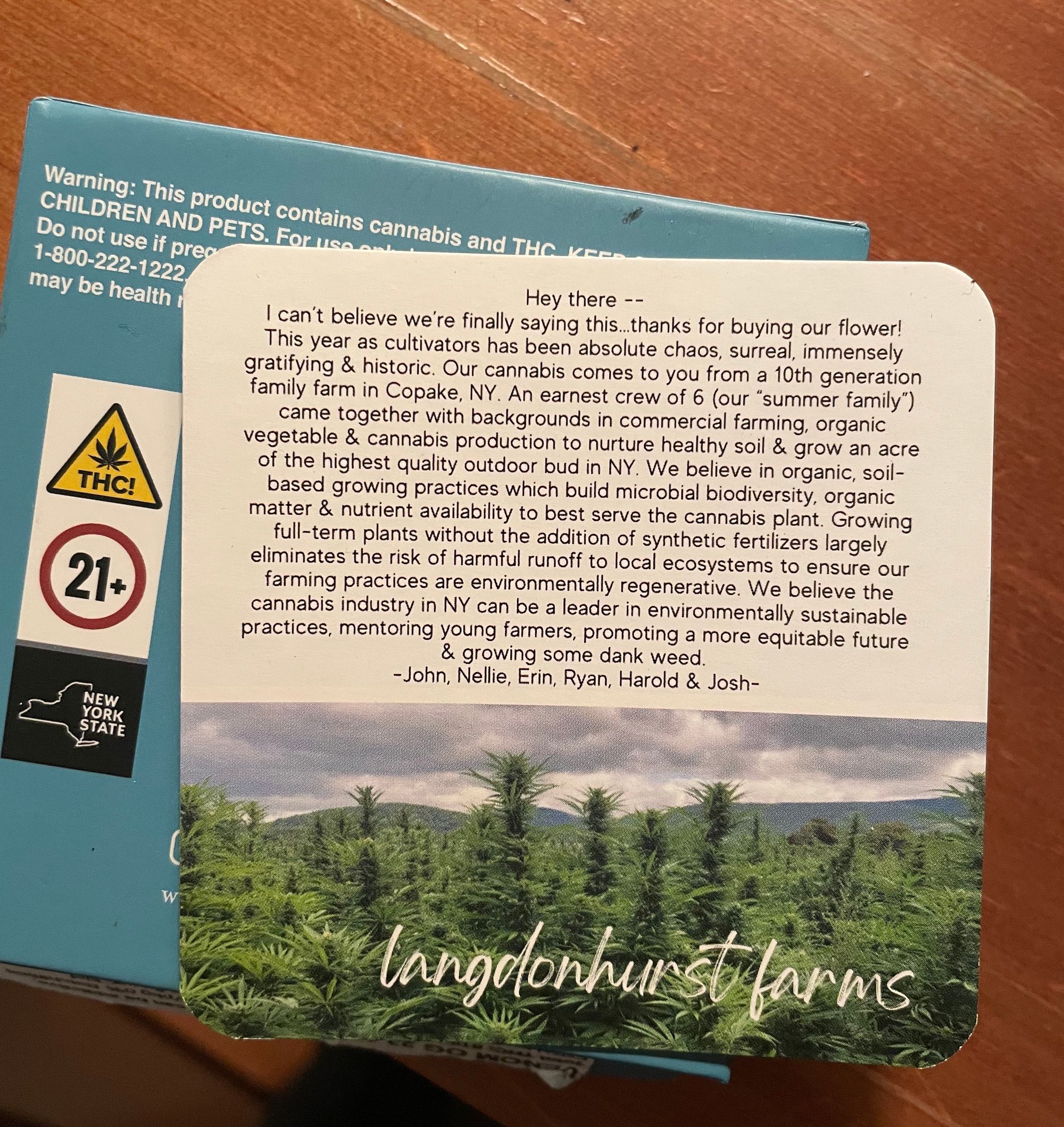

If you’re feeling adventurous, you can also trek upstate to buy directly from growers at one of the state’s authorized grower showcases.

"I know very few Black or brown residents who have been given a license."

‘Let’s use this as a reset’

Despite the idealistic intentions of lawmakers to, people of color makeup just one-third of all OCM licensees. These delays should give state and industry officials the opportunity to renew their commitment to the law, Cooney hopes.

“I want to give credit to the OCM for prioritizing and staying true to the legislation’s main intent, which is less about legal cannabis and more about giving back to families and communities impacted by the war on drugs,” he explained.

“Let’s use this as a reset moment. Let’s get the licenses out. Let’s allow social equity groups to apply. I know very few Black or brown residents who have been given a license, either at the processor or cultivator level.”

Comments ()