Backstage at Miss Subways, a vintage pageant reckons with a changing city

Contestants say a former 'everygirl' beauty contest 'could reflect the city better'

See more about this story, including a music video premiere, in this members-only bonus post.

Last Friday night at the Sideshows by the Seashore on Coney Island, a 70-year-old contortionist folded herself into a pretzel to the tune of "Take the A Train;" an Australian in gold tulle and a rat mask performed her remix of "Rapper’s Delight" and a mermaid opera singer belted an aria about reading smut on public transit.

This could only be Miss Subways, the homegrown New York City competition unlike any other. Almost 85 years after its start in 1941 as an ad campaign, it’s taken on different forms in its various iterations, but still highlights the best of New York since the City Reliquary revived it in 2017. And despite the commercial roots, Miss Subways has a historic legacy: it was the first racially integrated beauty contest in the world, crowning the first Black Miss Subways in 1947.

This year’s contestants were mostly full-time performers, a shift from the early days, when organizers sought "subway-riding everygirls from all boroughs: secretaries, servicewomen, sales clerks" according to a 1971 piece in the Times, which also called the contest winner “a queen whose realm is a hole in the ground."

Accessibility was the point: anyone could win (though not without organizing, more on that later). It’s still technically true that anyone can run for Miss Subways, but the vibe now tilts toward showmanship. I overheard one audience member saying, “Do they love New York, or do they love performance and they’re using this as an outlet for their performance?”

This year’s prize at Friday night’s competition went to the Australian in gold tulle, Bimini Cricket, a “nerdylesque” performer and professional mermaid. Cricket’s dedication to the city stretches to wearing a giant rat mask around the streets during a heatwave to film a video for the contest.

“I got catcalled,” she told The Groove. “Well, ‘ratcalled,’ I suppose.”

Bimini won for her energy, impassioned answers to the interview portion and custom-made music video. She remixed "Rapper’s Delight" to "Ratter’s Delight," where she celebrated the subway system in a music video packed with puns and transit trivia, all in an oversized rat costume.

“To be Miss Subways, you’ve got to love the city and the diversity you find underground,” she said. As an example, she recalled seeing a woman faint onto the tracks last year.

“The train was only a minute away. It was so scary, but so many people jumped down to the tracks to help her,” she said. “When she got back on the platform, everyone circled around to take care of her, gave her snacks, water, one lady used her leather purse as a cushion, another held the fainter’s head. Everyone in the circle looked different from each other. Honestly, I work in casting, and if this was on TV I would have said it was unrealistic. But it was real.”

Diversity is part of the pull of the contest, with City Reliquary’s official call for contestants stating: “The event expands on the progressive history of Miss Subways as the first racially integrated beauty competition and invites contestants of all gender identities, body types, and ages 18+ to apply.” Previous winners have included multiple queer contestants and at least one “post-menopausal” Miss Subways. In this way, the pageant has evolved with the best of the city. The modern contest welcomes train-loving sickos of all kinds. But in other ways, it may reflect other trends in the city.

Miss Subways 2024 Queerely Femmetastic was at this year’s show to hand off the transit tiara. She was proud to be part of the lineage of the first integrated beauty pageant, and suggested organizers could do a better job of reaching out to potential contestants from all walks of life.

“The pageant could reflect the city better,” she told The Groove.

Still, the pageant has become a proudly offbeat annual event, an ode to (or sometimes roast of) the subway, and a celebration of both the people of this city and what makes it move. The Groove hopped backstage this year to get up close with the contestants, and take a closer look at the show’s past and present, and some ideas for where it can go next.

The Groove just turned two years old! Help us celebrate two years of worker-owned, independent local journalism by becoming a member today. You'll unlock bonus content and sweet perks too.

From poster to ‘pin-up’ to platform

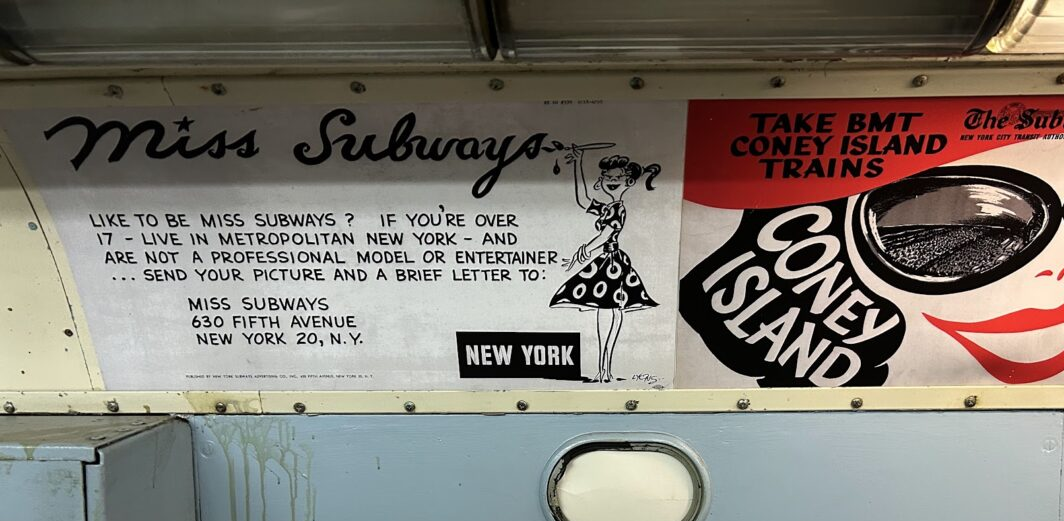

Miss Subways began in 1941 as a marketing gimmick, not a stage show.

“The MTA made money on it!” a spokesman for the agency told the Times in 1979. Run by the New York Subways Advertising Company in conjunction with the first-ever modeling agency (John Robert Powers), headshots of beautiful women on subway posters drew attention to nearby candy, cigarette, and cod liver oil ads. These women became overnight celebrities. The first Miss Subways received no less than 258 marriage proposals, “one orchid a day for six months from one smitten rider” and a three foot wide lemon meringue pie.

Originally, this was a beauty contest in which the only requirement was to be “a New York City woman who rides the subway.” Powers himself handpicked contestants until around 1963, when the contest shifted to a public vote by mail. With that change came a shift in image: “Prettiness per se is passé. It’s personality and interest pursuits that count,” said Bernard Spalding, spokesman for the NY Subways Advertising Company in 1971. He supervised the contest for its last 14 years and commented that “the contest now aimed to reflect the girl who works, what New York City is all about.”

Posters highlighted each winner’s personality and goals. One journalist who grew up seeing them commented on how inspirational they were. “What I waited for each new month was: What did she do? What were her goals?”

The contest was ahead of its time in terms of representation, partly because of its singular requirement, partially because of New York residents. Within the first few years of the contest Powers was pressed by various ethnic groups of New York about why he wasn’t selecting someone from Jewish, Italian, Black, or Scandinavian groups. Early on, Jewish contestant Enid Berkowitz Schwarzbaum noticed: "Somewhere along the line it occurred to me I had never seen a clearly ethnic name on that poster. "My name was distinctively Jewish, and that might have been part of the reason I might have said let's give it a shot. Let's see what happens." She ended up winning the 1946 title.

The next year, 36 years before Vanessa Williams became the first Black Miss America, New York crowned its first Black Miss Subways. The 1947 win was the result of coordinated civil rights efforts: Black social clubs submitted photos, organized letter-writing campaigns and contestant pools, and directly pressured Powers. Miss Subways represented more than train posters.

One advocate wrote in a letter to the editor, “This is not just a question of getting a Negro girl chosen as Miss Subways. This can be the beginning of getting pictures of Negroes in our magazines, newspapers, subway ads, and more.” Thirty years later, Ms. Hocker, a winner from the 1970s, asked organizers to darken her photo for the subway. Though Black, she worried “I looked too light; I didn’t want any confusion,” she said. “People can say, ‘That’s one of us.’”

This representation was uneven. Two years after Thelma Potter’s win, the first Asian Miss Subways, Helen Lee was selected. Her poster was labeled “exotic,” and she ultimately resigned (the reasons are unclear). The 1954 Miss Subways, aspiring physicist Juliette Rose Lee, was labelled “petite."

As New York changed, impressions about the contest did too and it ended in 1976 with concerns of sexism. Spaulding said in 1971 that Miss Subways "was a World War II pinup phenomenon and then lost social significance.” He added, “we got a lot of flak from women's groups that wanted to change it to Ms. Subways, or Mr. Subways.” When people asked for the contest back in 1983 an MTA representative called it "irrelevant and socially unacceptable.”

But not everyone agreed. Miss Subways left a pop culture legacy too. I first learned about it through a book I stooped, written by native New Yorker David Duchovony. A retelling of a W.B. Yeats play, it features a New York city teacher who’s helped by mythical figures on her journey to love.

In 1974 Cher sang the praises of the fictional, aging Miss Subways of 1952. who “even had some cousins who couldn't stop throwing themselves at her feet."

The 1944 musical On the Town uses Miss Subways as a plot device, centering on a sailor’s search for "Miss Turnstiles.” And in The Nanny, Fran Fine claims she was a former Miss Subways herself (“Tattoo”, Season 4, episode 9).

A sampling of this year's contestants. (Photos by Seemal Karthik)

Portraits of past winners line the walls at Ellen’s Stardust Diner, owned by a former Miss Subway herself, 1959’s Ellen Hart Sturm. She often hosts Miss Subways reunions at the diner.

The contest returned in 2004 for the subway’s centennial, with posters that featured subway safety tips instead of bios. It was brought back again by the City Reliquary from 2017 to 2019, paused for the pandemic, and returned in 2023.

Taking the A Train

Last year’s winner, Queerely Femmetastic, said her title came with perks.

“It's been so fun, getting invited to different events, getting to wear my sash, the cops letting me in on the train for free when they see me,” she said. “I'm not gonna say no, that's $3!

She first heard about the pageant from her grandma. Queerely Femmetastic’s act last year also involved the Duke Ellington Classic "Take the A Train," with the performer rewriting the lyrics to reference a changing New York.

“Take The A Train" was written during the Harlem Renaissance when a lot of people were moving to New York from other places, but couldn't afford to live uptown in Harlem, so they lived in Brooklyn, in places we now call Bed-Stuy, Crown Heights. Those folks were going up to Harlem to go dancing. That's where the socializing was, well, at least socializing for them. And so the song was written about this rush to get uptown.

Now, she said, the opposite is true.

“People live all over New York, especially Black folks live all over New York,” she said. “But a lot of the social activities that people wanna go to are in lower Manhattan and Brooklyn. So it being a little bit of a comedy sketch, I talked about making sure that you get the last express train before 11 o'clock. Don't get on the E or else you'll end up in Queens. Like a kind of reference to how the city is changing.”

This year’s contest, she noted, had changed in a less encouraging way.

“You know, Miss Subways was the first integrated beauty pageant in the world and that is so, so, so important when you think about this city's history,” Femmetastic said. “I gave this feedback to City Reliquary, but in the past, the contestants have always been a wide range of people. This year there was one person of color in the entire cast, and there were no Black and brown contestants. This year there was one native New Yorker, when last year there were four or five of us. In this city and in this political economy?”

She suggested the idea of a search committee, and reaching out to previous contestants so that more people could hear about the contest.

“A lot of what makes the contest good is that it's people from all walks of life,” she said.

Cricket said she has a personal goal of making people more aware of the competition, which she hopes will lead to more diversity.

”Diversity was definitely a little lacking this year. I don’t know how diverse the applicant pool was,” she said. “And as a white woman that was born in Australia, me winning may not be helping the situation. But I would argue that NYC is a melting pot, so why not have an Aussie Miss Subways? I identify as a New Yorker, and I think you can claim that title the first time you successfully help a tourist with directions, or the first time you really experience rage over a tourist blocking the sidewalk.”

The pageant used to be monthly, now it’s held once a year in Coney Island. It’s no longer affiliated with the MTA; judges, not the general public, pick the winner. And perhaps most notably, posters of the winners don’t run in the subway. But the core fun remains: a chance to engage with people who love this city and celebrate the subway, which does deserve a crown of its own.

Mayor Ed Koch once said: “Even now, I can sit in the subway, and look up at the ads, and close my eyes, and there's Miss Subways. She wasn't the most beautiful girl in the world, but she was ours. She was our own Miss America.”

Comments ()