‘Don’t lock up the trash!’ say the recyclers

Containizeration rules could leave canners without two nickels to rub together

One morning this spring, empty bottles and cans clattered, stabbing the early quiet on north Brooklyn’s Flushing Avenue, an industrial strip flanked by nightlife. A 35-year-old Senegalese man and two friends from the nearby refugee center stood by a rolled up gate, waiting their turn to give their hauls to the employee at the open garage door.

The man, Mor Talla Diop, came to New York City to find a job. After traveling across four continents, he watched others rummage through bins for empty cans of Modelo and Liquid Death that could be recycled for cash. He didn’t think it was hard to learn how to do it too.

Some canners drive vans laden with bulging, large-scale bags full of redeemable containers. Diop walked. At his feet were two mid-sized, half-full plastic bags. He borrowed a Sharpie from the redemption center worker and marked the count on each. After 11 hours, he’s gathered enough to earn $5 in cans and $3 in bottles.

Diop equips himself with a pair of polyester gloves. Each can is light, but they add up, as do the hours.

“It’s difficult,” he said in French, repeating, “It’s difficult.”

The city has made big promises, and some big moves, about containerizing trash this year, in an effort to get loose bags of garbage off the curbs and combat the rat population. Those moves could also cost folks like Diop their livelihoods.

The Department of Sanitation calls its containerization plan a “Trash Revolution.” For the layperson, it’s the life-changing magic of putting garbage in hard bins instead of leaving rat takeout loose on the sidewalk, as the city has done for generations. By Nov. 12, everyone living with nine or fewer units in their building will have to use a wheelie bin for their refuse.

Next summer, the DSNY will test “European-style” bins for behemoth buildings (31+ units) in Community Board 9 (Morningside Heights, Hamilton Heights, Manhattanville). Buildings with 10 or more units can choose between the two available containerization models. All businesses were required to containerize their trash in March.

The problem? As Sanitation courts contractors for these Continental-inspired dumpsters, they want designs to include fancy, RFID-card-or-similar locking mechanisms. That could lock away at least half of all residential refuse — and block the income of people who earn their wages five cents a time, can by can. Those people are often the workers who make sure recyclables end up getting recycled at all. Those canners want the Department of Sanitation to meet with them and take their jobs seriously — and assure them the new cans won't lock them out.

“We want to be taken into consideration,” Josefa Marin, president of the Alliance of Independent Recyclers of NYC, said through a translator. “We consider ourselves to be an important stakeholder in terms of recycling and improving the environment of the city.”

Locking the new trash bins would help prevent illegal dumping and trash from spilling on the ground. But it could also mean much of the city's recyclables won't get saved from the landfill.

Ryan Castalia, executive director of the nonprofit redemption center Sure We Can (SWC), said their local canner coalition has been trying to meet with Sanitation Commissioner Jessica Tisch since the beginning of the year. A Department of Sanitation spokesman wrote in an email to The Groove that the leaders at the department “do not oppose any New Yorker redeeming cans and bottles to make ends meet.”

Canners are growing in number

Castalia said canners’ relationship with Sanitation is warming somewhat. City code does still say that messing with trash bags placed at the curb for collection can result in a fine of $100 to $300. Fines go up if you use a motor vehicle, so most workers stay on foot.

The number of canners may be increasing. Canner anthropologist Christine Hegel, from Western Connecticut State University, released a recent survey of this workforce, co-published with the Alliance and SWC. Her team found that the city has between 4,000 and 8,000 canners, also called waste pickers or lateros in Spanish. They are twice as likely as an average New Yorker to have emigrated from another country. Although she didn’t count the city’s recent refugees in their study, Hegel noted that her team sees more canners in every borough, most notably from the West African country of Mauritania.

A few blocks from Diop, waste pickers have their own clubhouse. After more than 15 years, SWC owns their own East Williamsburg redemption center. There, canners sort their wares and organize their labor. To qualify for a nascent international coalition, in 2022 SWC incubated a collective that became the Alliance of Independent Recyclers of NYC.

One-cent profit

Over 20 years, Josefa Marin built a routine, complete with regulars and a white cargo van. In 1988, she immigrated from Mexico to help make money for her family, six years after the first bottle redemption law was passed. The nickel redemption rate hasn't changed since.

Marin naps in the van while her husband, Pedro Galicia, waits at SWC for their next call from a bar. At 4 a.m., a nearby nightclub closed, marking the beginning of their workday. Marin explained that they buy cans from people who live on the street, who collect them from bars and elsewhere. Galicia said he prefers paying his suppliers, because they perform work for him and payment makes them more reliable. Marin added that otherwise, the unhoused collectors are vulnerable to theft. Sometimes, their profit margin between purchasing the empty can and redeeming it is one cent, sometimes more.

Hegel’s study found that two-thirds of waste pickers have people in their lives who save cans for them, out of kindness or a desire for a cut of the proceeds. Like other waste pickers, Marin and Galicia have diverse sources, from loose cans to bars that let them come in to pick up after closing time. They collect at night and early morning and usually sort at SWC, their “second home,” from 8 a.m. until 5 p.m. They take some Wednesdays off, but only during the daytime.

Galicia, another long-established migrant from Mexico, assesses their haul. The couple brought in 11 bags of 400 pieces each. Galicia estimates they make more than $150 per day.

"Starting from zero, it's difficult at first," Marin texted later, in Spanish, "But I feel like I've already achieved what I came to do."

New Yorkers still suck at recycling

Sanitation accounts for canners in its Waste Characterization Study, where the department counts what New Yorkers throw out. The most recent study found New Yorkers still suck at separating their recyclables. Even with waste pickers pulling redeemables from trash bins, three out of four aluminum cans end up landfill-bound — an increase from other years.

“We deserve the right to do something that is healthy and clean for our environment,” said Alliance secretary Yvonne Norville.

She added that waste pickers make Sanitation workers’ jobs easier by removing redeemables from the waste stream. Recyclables can also cost the city more than trash to process.

No one needs a special license to return a bottle or can. Some lateros have high-vis vests, gloves, and private garage spaces. Some might have a rolling laundry cart.

Are you throwing nickels away?

Since 1982, the state’s “Bottle Bill” sets the refund rate of a nickel per beverage container. Almost any carbonated drink, beer, sugar-free water or wine product container counts along with plastic bottles of water. Wine bottles, milk, hard cider, and flat drink containers don’t usually merit five cents. The drinker pays that money at the cash register and may bring the can or bottle back to any store that sells the same drink. The store gives the refund, which is covered by the drink distributor. The city collects most of the unclaimed deposits, usually more than $110 million per year.

The alliance’s treasurer, Rex William, Jr., learned how to can when he was a child. Now 48, he remembers his grandmother stuffing her Queens space with bottles and cans to redeem, adding, “She was cool.”

William said he and the other Fort Greene lateros work in mutually agreed upon shifts. He’ll bring in maybe $80-85 per day, usually limited by how much stores will let him redeem at a time. Larger retailers may cap their refunds at 240 containers per day. William might go to his local grocery store three times to line up with their shift changes, at $12 per round. But, he needs to stand in line with other shoppers, cutting into his hourly rate.

Retailers are required to accept any kind of redeemable container that they sell. They have fought that policy, not wanting the headache or responsibility to store cans and bottles. Smaller retailers may limit their redemptions to 72 per day, but theoretically canners can make appointments in advance for unlimited refunds. In practice, canners such as William and Diop rely on commercial redemption centers, who get 8.5 cents from the bottle distributors and pay the canner five.

No longer considered 'scavengers'

North Manhattan native and chair of City Council’s Sanitation Committee Shaun Abreu helped bring the containerization pilot program to Morningside and Hamilton Heights last fall, which he represents. The program led to 68% fewer rats spotted.

“That was not a campaign promise, but it was a promise for my girlfriend,” he joked, recalling her jumping as they walked the city.

Abreu later said that he met with SWC – venturing to Brooklyn – and will work to accommodate the canners' demands that containers will not be locked.

Castalia sees the changes as coming top-down from the Department of Sanitation and wants waste pickers to have a seat at the proverbial table. The SWC director said that he learned about the proposed containers on the news and wishes there had been a discussion or hearing.

“It seems like the city kind of skips [discussions] and has gone straight to the implementation phase with a lot of these pilots,” he said. “Historically, canners and the DSNY have been somewhat at loggerheads.”

Castalia hopes that will change.

“It wasn't that many years ago that DSNY and its partners were calling canners ‘scavengers’ or saying what they did was illegal,” he said. “That's not happening anymore.”

Sanitation, SWC and the Alliance all underline that they want to keep the city clean and send fewer recyclables to landfills. Marin, Castalia and other Alliance leadership said they’ll keep pushing in Albany for a raise in the refund value. If she’s asking for the moon, Marin thinks it would help if the city could provide canners with gloves and protective gear. But really, organizers say, they just want the Department of Sanitation to keep the new bins unlocked.

Otherwise, it will be a drastic shift in what has become a routine for pickers like Galicia. He says that his wife, Marin, “changed my life” when she taught him how to can. Before that, he thought of it as disgusting work. Afterwards, he started seeing potential nickels on every corner. Now, they work together just about every day.

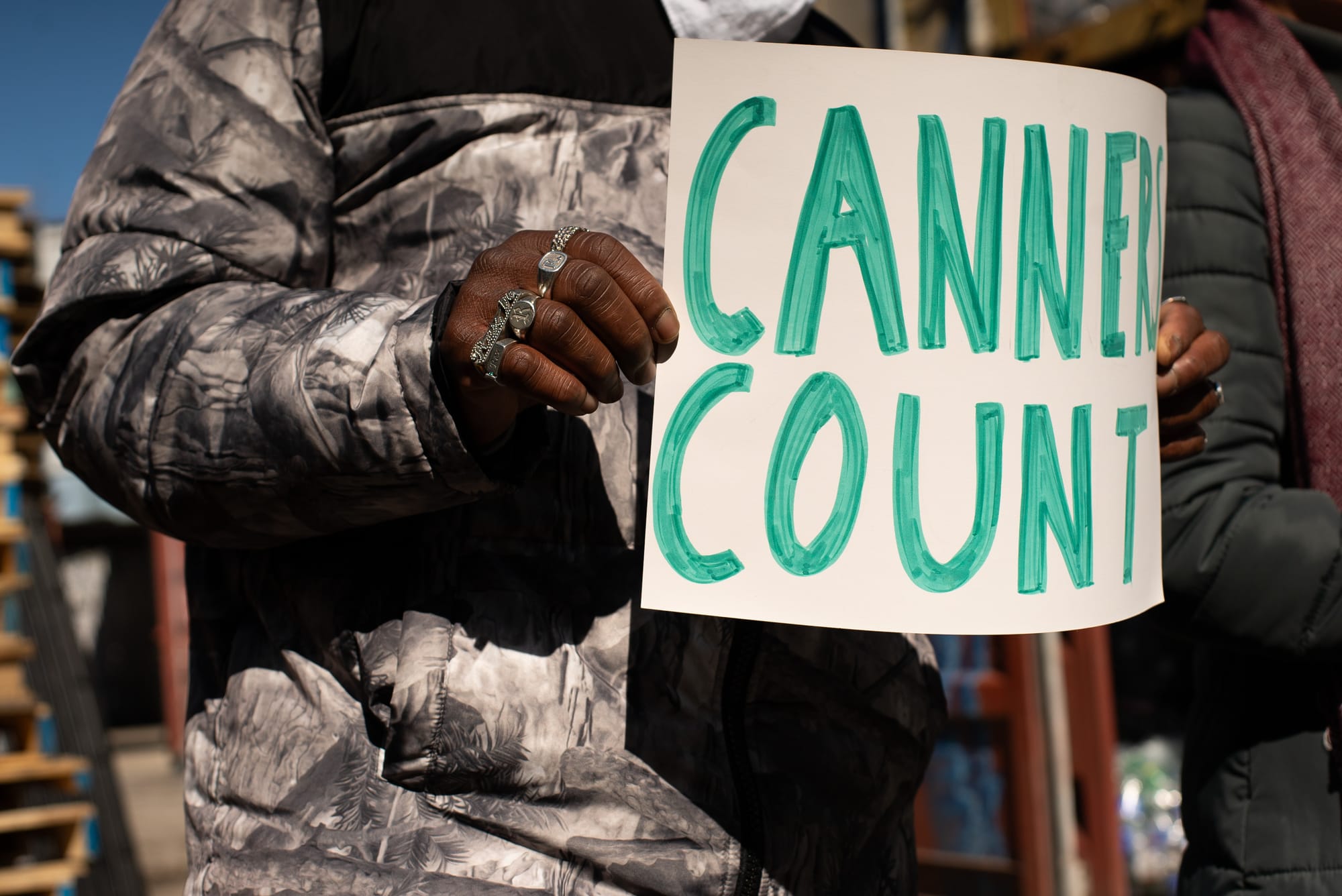

On International Waste Pickers' Day (March 1) this year, SWC held a rally to bring attention to their labor organizing, advocate for a raise in the refund value, spotlight the potential locking of containers and publicize the new study. The group put out milk crate chairs and noisemakers made out of beans inside empty cans. Marin spoke to the roughly dozen lateros, some holding signs that said “Canners Count” in English and Spanish.

“This is hard work. We walk the streets at all hours of the day, for hours at a time, collecting our income five cents at a time,” Marin said in her speech.

They had gathered between the caverns of piled blue and clear bags with cans separated by color. After her speech, she would go back to sorting heaps of cans much taller than her.

“We've been excluded for so long," she said, "but we're here, we matter, and we need to be kept in mind.”

Comments ()