The ‘pigilante gang’ takes on an alleged BK pigeon thief

Is someone stealing street pigeons and selling them to gun ranges?

On Saturday afternoon in Bushwick, a man in a purple hoodie emblazoned with pigeons stood nose-to-nose with a young woman clutching her phone, both screaming. Behind the man, inside a pet store, employees and customers were cheering him on, one with a trained pigeon doing flips on his shoulder.

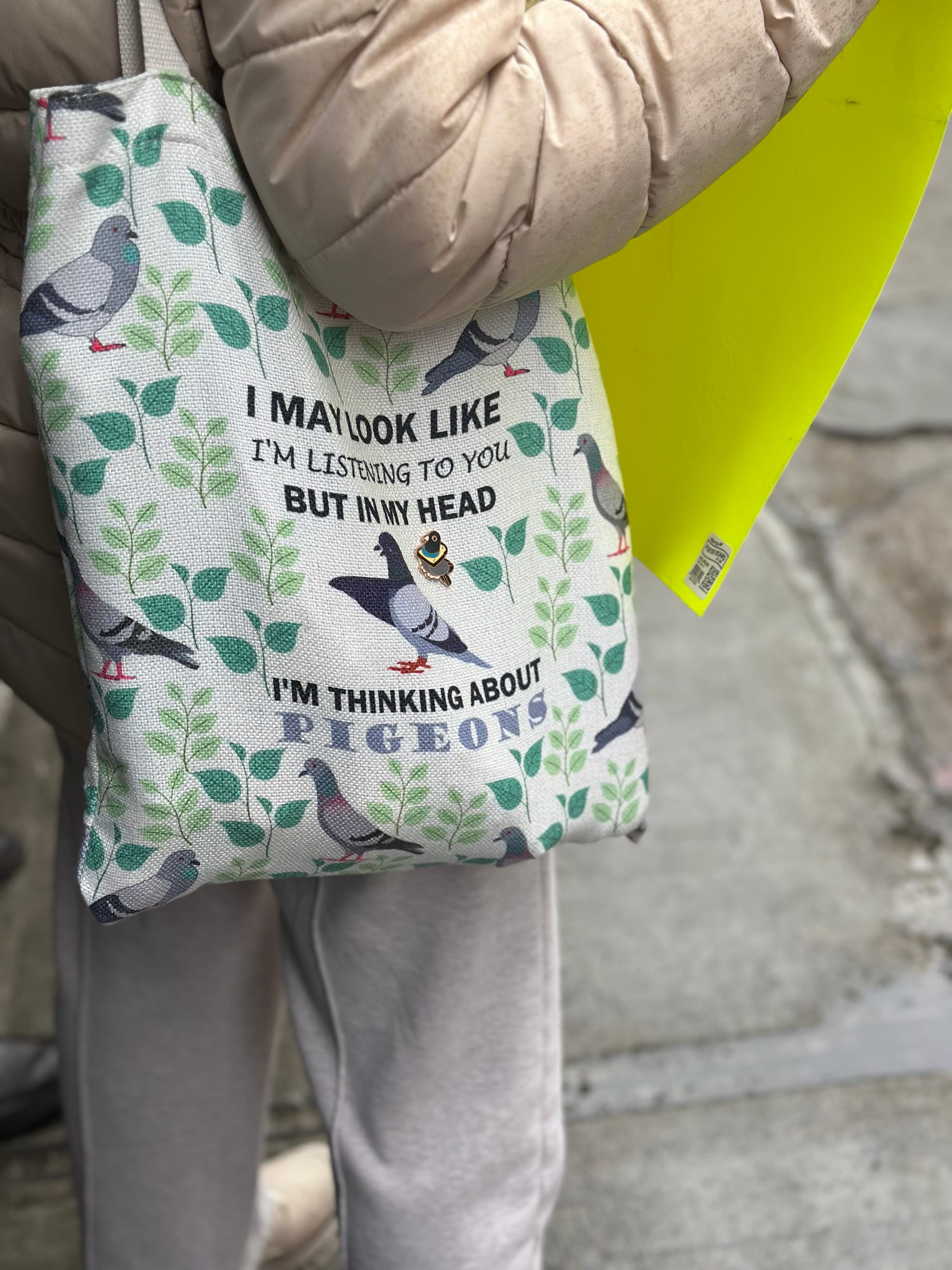

Behind the woman outside the store, a small crowd of other New Yorkers, some wearing head-to-toe pigeon costumes or pigeon makeup, held protest signs and chanted. The screaming had started when the man had caught the woman snapping a photo of his van’s license plate; he ran inside the car to blast Spanish music at full volume, opening all the windows and doors, despite the cold rain, for maximum impact. Inside the van were stacks and stacks of neon yellow sacks of pigeon feed.

He then lunged from the car and screamed: “If you post my picture online, I’ll beat the shit out of you.” The woman, a pigeon rescuer named Megan Walton, responded, “Can you say that again?” The man screamed, “Suck my dick!” She returned “You think I care, you toothless fuck?” People from both sides stepped in before feathers really flew.

This isn’t your average sidewalk dispute over a parking spot: this face off is about none other than the humble rock dove, more commonly known as the pigeon, the birds often disparagingly called rats with wings (admittedly, I’m biased, I do pigeon-focused walking tours and am an avid pigeon watcher). The showdown is unfolding in front of Broadway Pigeon & Pet Supplies, a mom-and-pop pet store on Broadway in Brooklyn, between Bed-Stuy and Bushwick.

"They definitely targeted the wrong flock this time, because that was Mother Pigeon’s flock.”

Protesters claim the owner of the store, Michael Scott, has kidnapped pigeons off local streets and sold them off to become skeet shooting targets in Pennsylvania. The store denies the claims, saying they’re being targeted by rivals, that they’re not responsible for what happens after pigeons are sold, and that they love pigeons. Protesters blasted Scott with theme music for The Office repeatedly.

In New York, it’s illegal to trap or net pigeons on public property. On private property, only licensed exterminators can request a permit to trap on private property. Otherwise, the city considers it animal cruelty.

“It’s happening all over the city,” said Walton, who runs a small pigeon sanctuary in Putnam County. “Union Square Park, Washington Square, Father Demo Park, Brooklyn, Queens … they target the feral flocks, the ones nobody’s watching. They definitely targeted the wrong flock this time, because that was Mother Pigeon’s flock.”

Leading the protest with Walton was Tina “Mother Pigeon” Piña, a street artist and self-appointed avian guardian angel, recognizable by her usual pigeon fascinator, or otherwise full head-to-toe pigeon costume. You’ve probably seen Piña before, especially if you’ve passed through Union Square. Since the late 1980s she’s made interactive public art about pigeons by knitting life-sized pigeons as a form of urban folk art.

The protests this weekend began in response to the netting of her own pigeons from Bushwick’s Maria Hernandez Park on the morning of April 1: eyewitnesses told her they saw the birds being netted from where they regularly roost and stuffed into a van. But as Piña and others stress, this protest isn’t just about a single flock of birds being stolen, it’s about an underground pigeon trade facilitated by a self-proclaimed pigeon advocate and a city that ignores these birds, their history, and the fact that they’re now vanishing.

“We definitely always expect high tension and high emotions and things like this,” Walton said about the protest. “But I think it's actually very important to go out there and show them that we are rightfully angry … they shouldn't feel comfortable at these events. That's the whole point of protesting. ”

It wasn't all screaming at Saturday's protest. (Video by Jess Joseph)

And in response to the store’s claims of innocence, she said: “They say they love pigeons, but they love exploiting pigeons. They love using them for money, whether it's breeding them for races, or those event releases, or snatching ferals to sell them. They love pigeons because of what pigeons do for them or how they use them. We love pigeons because we truly love them. We want to see them happy, free and safe. That's what love is.”

Flight risk

Rumors of pigeon poaching have swirled for years among those in the know. Pigeon rescuers, photographers and artists (the “Pigilante Gang” as Tina refers to them) say this has been happening for decades, often tied to Broadway Pigeon. Activists have surveilled, protested, and even gone undercover (one time, in a nun costume) to investigate.

Ten years ago, a big flock of about 300 pigeons was netted in Washington Square Park, Piña told The Groove. She held a memorial for those birds.

Since the 1980s, the story’s been the same: vans with covered license plates lurk by parks; a man jumps out with a net and pigeons vanish in a flurry of wings. “Netting season” in New York is whenever a Pennsylvania pigeon shoot is coming up, which is often. There’s no official season: these shoots are privately run by gun clubs, not state-regulated, and usually happen on private land.

“They collect the pigeons right before the weekend of the shoot, and then the pigeons are all gone,” Piña told Brooklyn Magazine. After that, you might as well be looking for a needle in a haystack (or a pigeon in Pennsylvania).

Activists say they’ve filed dozens of 311 reports, but the NYPD and the Animal Cruelty Unit do nothing.

Most city pigeons aren’t wild; they’re feral, descended from once-domesticated pets. Mother Pigeon’s flock that she cared for in Maria Hernandez Park was a mix of feral birds and rehabbed rescues, which meant their absence was noticed. After they vanished, she rallied the rescue community online and teamed up with independent rehabilitators to plan a protest; about 60 people showed up to shame the alleged snatchers.

Pet Shop of Horrors?

At the center of the controversy is Scott, a middle-aged Brooklyn (not Scranton) native and lifelong pigeon fancier, and the family business he runs. Broadway Pigeon & Pet Supplies doesn’t look like much from outside, but inside you’ll find a huge collection of pigeons including a few of the exotic kinds that put you in uncanny valley territory, with more on the roof. You can buy bird supplies or the birds themselves, from about $3 to $20 or more for specialty birds.

In New York’s pigeon subculture, Scott is a known figure who’s been profiled as a “pigeon guy” in the local news, painted as a Brooklyn bird whisperer who fell in love with pigeons as a kid and now keeps dozens in rooftop coops. Scott is involved in the insular world of pigeon hobbyists in Brooklyn, the folks who race pigeons, breed fancy varieties or keep flocks just for the joy of it.

Scott has gone mildly viral on Tik Tok and Instagram because of Broadway Pigeon: one popular video is framed as “do you ever walk past a store and think, how do they make enough money to stay open?" In the video, Scott explains that owning the building helps, but most of the income used to come from selling pigeon seed when raising pigeons was a much more popular hobby. As that changed, the store started to sell pet supplies and other kinds of birds, and started renting pigeons out for release during funerals and weddings.

Scott claims that these birds “fly right back;” pigeon rescuers say that’s untrue, and that only 30% of released birds make it back, because businesses usually release them at too young an age to have developed a homing instinct. These are many of the birds that amateur rescuers rescue and rehabilitate.

The real profit might actually be in trafficking pigeons. There’s good incentive to do so, because as the Humane Society told the Post for a 2008 report on the issue, the birds illegally netted by poachers from parks and sidewalks are sold to a retailer or go-between for $2 a bird; the retailer then wholesales the birds for $4.50 each to a broker, who then resells the birds for $9 each to a gun range.” That’s netting a high profit — and that was in 2008 dollars.

That’s partly why the accusations are ruffling feathers. If Scott’s been netting pigeons, it means the call is coming from inside the coop.

“Mike breeds the birds upstairs. Mike takes better care of the birds than he takes care of himself,” said one man hanging around the shop.

A few hours after the protest, once he’d finished feeding the pigeons he keeps on the roof, Scott rolled his eyes when I asked him about the allegations.

“They got three different people netting pigeons in the street. Do any of them look like me?" he said. "One's a short Asian guy. The other's a short Spanish guy ... Do I look short, stocky, young to you? I’m 6 foot 2, I’m old, and fucking white as a ghost. I don't pay attention to these people.”

He claimed to have “no idea” why anyone would accuse him, what motive they might have, or why they’d think this at all.

“Maybe they don’t like people who keep pigeons," he said, "I don’t know.”

He then pivoted to Walton, the activist, and claimed she was a scammer with an illegal nonprofit, saying, “I’m not the one with the sanctuary putting shit on social media when I haven’t paid my taxes or filled out the proper forms and everything.”

He flipped open his phone to show me old clips from Walton’s Instagram, saying, “This video is nine years old,” offering no other context about issues involving Broadway Pigeon.

“Look,” he said, “I spoke to my attorney this morning. We need to find out who these people are that’s making the post. Then we need to conduct an investigation to look into their assets. Then we need to cause havoc on everything around them.”

When I asked if he planned to take legal action, he didn’t hesitate: “Yeah. Oh, I’m going to have fun.”

But Scott didn’t mention the documented history that makes these denials dubious. Back in 2008, amid similar accusations, the vice president of the Humane Society of the United States referred to Scott and his brother Joey Scott as “brokers.” At the time, the brothers’ attorney Joseph Mure admitted to the New York Post that the shop had sold live birds to a broker who worked with a Pennsylvania gun club.

While Scott wasn’t caught netting any pigeons himself, Mure said at the time that a Don Bailey (a man in charge of an invitation-only tournament at Strausstown Gun club) “has purchased birds from the store in the past,” and that Broadway Pigeons had bought birds without verifying whether they were illegally captured.

“He’s got no idea of whether any of the pigeons he’s purchased were netted,” Mure said, adding, “When someone comes in and buys pigeons, my client doesn’t know where they go.”

Indeed, selling a pigeon you raised and not knowing what ends up happening to it isn’t against the law. Who knows what people are doing with what you sell?

When asked later, the Mayor’s Office of Animal Welfare confirmed to The Brooklyn Eagle it has been coordinating with the NYPD’s Animal Cruelty Squad to investigate the pigeon-poaching allegations.

From Brooklyn to the blood sport capital

Pigeons are not native birds, so they’re not covered by federal laws like the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. In Pennsylvania, “all birds are protected by state and/or federal law, except pigeons, house sparrows and European starlings” because they’re considered pests. It ‘s illegal to kill any other bird species without a special permit, which leaves pigeons fair game.

Pennsylvania’s pigeon shoots rely on both a loyal base of shooting enthusiasts and a steady supply of birds. Stealing them off city streets is quick, quiet, and convenient for shooters who need hundreds of live targets per event. Why breed when you can net?

Pigeon shoots are rough. As described in a Pennsylvania state bill introduced in 2024 to ban the practice: “in pigeon shoots, live birds who have been captured and kept in dark boxes are released into the air to be shot by participants in a contest. Observers estimate that 70% of the birds are wounded but not killed outright. After each round of shooting, wounded birds are collected, often by youth with no training in proper euthanasia methods, and are killed by slamming, snapping or snipping the head off, or by breaking the neck. The birds are then tossed into a barrel or pile of dead and dying pigeons and discarded as garbage.”

But Pennsylvania, backed by traditional gun clubs and gun lore (Annie Oakley and Ernest Hemingway once shot birds too) clings tight. Even legendary game show host Bob Barker protested to get the practice outlawed, yet it still persists.

Last year, a bipartisan bill to ban pigeon shoots actually passed a state House committee, but that’s where it stalled. Just this week, Spotlight PA published an article looking into what was going on with the bill, as it routinely comes up in Pennsylvania’s legislature. They discovered that a prominent shooter’s association and a gun club funneled tens of thousands into campaign donations. The House majority leader, who got a cut of that money, quietly declined to bring the bill to a vote. So it died, and the shoots keep happening.

For folks like Tina Piña, that’s tragic.

“It’s a brutal fate for a bird as gentle as a pigeon,” she told The Groove.

And she’s right. These birds, once messengers, symbols of peace, war heroes, are now ghosted off city streets to become target practice in a countryside bloodsport. All while it flies under most of our radars.

Rats with wings? Or 'angels fallen from the sky'?

Spend enough time with pigeons (or the people who love them) and you start to see them differently. To rescuers like Piña, Walton and Amina, pigeons aren’t pests, they’re gentle, loyal, and deeply misunderstood. As reported in our own explainer, there’s little evidence pigeons spread disease any more than other city animals. You’re more likely to catch something from a fellow commuter. They’re hardy but not invincible: only about 10% survive their first year, dodging hawks, thread tangles, poison, dogs and being netted off sidewalks and shipped out to be gunned down in Pennsylvania. To their advocates, their survival alone is reason enough to fight for them.

“They’re like angels falling from the sky,” said Oksana, an enthusiastic protester. “They’re just trying to live.”

The fight takes flight

The Broadway showdown last weekend ended after about an hour and a half in the rain, with the next event planned for May 17th at 12 p.m. at the store. Activists are also planning two other separate events at Maria Hernandez Park and the new pigeon sculpture on the High Line.

“Next time, we want to double the numbers, 100 people at least. We’re going to get a megaphone,” Walton said of future plans. “Every day, more New Yorkers learn about the pigeon shoot pipeline.”

Just like keeping pigeons is a dying culture; shooting them might be too. Across the border, Pennsylvania’s pigeon shoots continue to be brought up in the legislature, and are receiving increasingly negative coverage. Video footage of shoots (often captured by animal rights groups using drones) circulates online, and Gen Z seems mostly disgusted by them.

“That’s the dream scenario,” said Walton after the protest. “Ban the shoots, and we won’t have to be out there in the streets screaming about birds in 30 degree weather.”

Nobody is planning to let up on Scott just yet. As long as pigeons are disappearing from city parks, the “Pigilante Gang” intends to be a thorn in his side, or at least a loud presence on his sidewalk.

If you liked this story, make a one-time donation to our tip jar. Subscribe to The Groove for free to get more stories like this directly to your inbox.

Comments ()