Remote learning robbed kids of the few hours of good snow we’ve had in two years

Students and parents defied the mayor to embrace a rare day of fun snow

A dad carrying two clean sleds entered Prospect Park on Tuesday and surveyed the Long Meadow. The park’s wide open area was thronged with children and parents, but most of that morning’s lush, fluffy snow had been beaten down to rivulets of brown mud, while other heaps of it had been rolled into messy snowmen speckled with dirt.

“Can you even sled still?” he asked a fellow dad dragging three kids out of the park.

It was 2:10 p.m. and school was technically still in session.

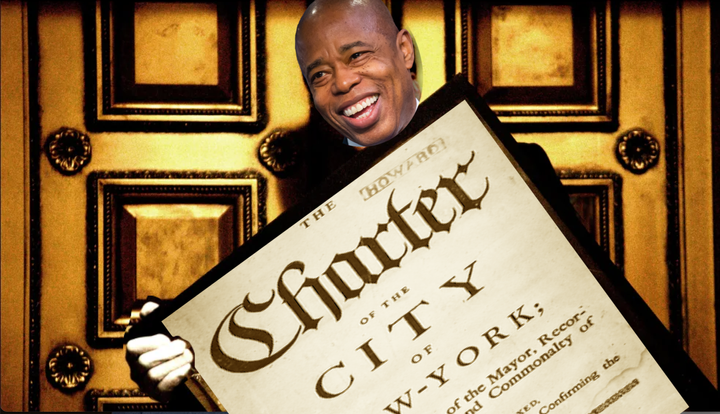

The city’s decision to functionally eliminate snow days since the pandemic in favor of remote learning returned this week, after a decree by Mayor Eric Adams that schools would be closed for the storm, but education would continue.

The decision was no match for technical problems that prevented kids from logging into the system anyway (if they even had a computer to use, that is); and it was met with derision pretty much across the board, especially after a record two years without any major snowfall. Teachers find it useless, kids hate it, parents bemoan the loss of a childhood ritual in favor of more screen time, even the childless DINKs of the city poured one out for the shorties who were short-changed of a sledding day.

Adams on Monday said: “Our children must learn. They fell behind. We need to catch up. That is what we need to be focusing on.” But instead of a full day of school, or a snow day, students got neither, and ended up with a half-assed attempt at remote learning that neither closed the gap in education nor would be made up at a later date.

But for the kids, there was one big lesson to learn that day: if you tried to do remote learning, you missed the short window of the few glorious hours of fresh, clean snow to play in before it all started to melt and turn to dirty slush not long after noon. It’s a brutal reality check on climate change but one that many parents seemed OK with teaching their kids in Prospect Park on Tuesday: if you miss the chance to play in the snow, you might not get another shot any time soon.

“Our original plan was to come out around 2, 2:30, so I’m glad we came out around noon,” said Jessie, a Prospect Heights mom whose two young kids were busy packing muddy snow into a tall makeshift igloo they had come across (“I think my kids are either trying to destroy it or add on to it. But they’re working real hard.”). Her 6-year-old daughter had logged on for about 30 minutes of remote school and completed an assignment before Jessie called it a day and decided to seize the snow while they could.

“I get that they’re trying to make it up and not have to tack on an extra day at the end of the semester, but I mean, this is part of childhood,” she said. “I don’t mind one random day of snow day.”

Some of the kids in Prospect Park weren’t even born the last time the city had measurable, sled-able snow; the changing climate means that snow might become increasingly rare in future winters too. The snow started melting nearly as soon as it stopped falling; by Wednesday, the clock on the city’s snowless streak restarted anew.

East Village snow report: 100 percent smud pic.twitter.com/yauS8HBMtV

— Gwynne Hogan (@GwynneFitz) February 13, 2024

Another mom said she gave her kindergartener about an hour and a half of school time before calling it in favor of snow time.

“They’re five,” she said, “they shouldn’t be on an iPad pretending to learn.”

One eight-year old managed to get to the park early enough to enjoy some fresh sledding hills, even if they were a bit taken over by speed-demon teens. Still, the specter of remote school hung over the day.

“I wish we still had old-fashioned snow days,” he told us. “Stupid computers.”

‘Pretty much a waste of time’

The cost-benefit analysis of taking a precious snow day instead of a glitchy, depressing remote work day isn’t just vibe-based. One teacher told us flatly that “nothing” is being taught on this kind of one-off remote day, a format that’s so far from anything resembling normal school that it should be reserved for only the most severe of weather events. Which, by the way, snow days used to be.

“Most teachers had them sign on for attendance, after 10 minutes let them go,” one high school math teacher in Jamaica told The Groove. “Even the principal didn’t really care. I saw him yesterday, he said, ‘Yeah it's a snow day, we're gonna pretend to do a little work, it'll be fine.’ ”

Whereas a traditional snow day would be tacked on to the end of the school calendar, this week’s attempt at a remote day will never get made up.

“It was pretty much a waste of time,” another high school English teacher in Manhattan told us. “My principal shortened our periods to 22 minutes and then had us hold office hours in the afternoon, but no one showed.”

Teachers working from home also dealt with the same child-rearing pressures that other parents dealt with.

“I had my 9-month-old baby at home with me. Thankfully my wife could also work from home today or else the baby would have been teaching the lessons,” the English teacher told the Groove.

New York City Schools Chancellor David Banks has openly said that the “remote learning” day was a failure, while Adams is busy dragging parents who struggled or declined to navigate the shaky remote technology as “a sad commentary.”

Remote learning or no, there’s an argument to be made that this entire snow day conversation should have been moot. After Mayor Bill de Blasio kept schools open during a 12.5-inch snow storm back in 2014, Gothamist crunched the numbers and found that historically, New York City snow days were few and far between, generally reserved for storms of up to a foot or more — nothing like the sloppy little slush pile we got on Tuesday morning.

The practice of pre-emptively closing public services over less than a foot of snow is one of the worst post-COVID outcomes of city life. We used to just....bundle up and carry on. pic.twitter.com/ZZXwYs85lU

— Marcel Moran (@marcelemoran) February 13, 2024

Even the older kids who weren’t eager to go play around in the first big snow in years found the day a bust.

“When I logged onto my link in the morning, the teacher wasn’t there, so I left,” one high school senior in Harlem told us. “Everyone wanted to use their day to relax and do what kids do when there is no school: lay down.”

Dave Colon, Tim Donnelly, Jess Joseph and Virginia K. Smith contributed to this report.

Comments ()