The lesson from Kim’s Video? Keep hoarding your physical media

A new documentary chronicles the deeply weird fate of the beloved local video store, and offers a blueprint for escaping your streaming fatigue.

There’s always a booming market for “New York used to be cooler” nostalgia, but the newly released documentary Kim’s Video happens to be landing in theaters at a potent cultural moment. Demand for dumb phones is bustling, teens are going full luddite, Blockbuster-style “little free libraries” of DVDs are cropping up, artists and listeners alike are increasingly leery of the music streaming model, cassettes are back, vinyl is back, everyone’s sick of paying too much for a million different streaming services, the list goes on and on. Maybe we’re all ready to get a little extra misty-eyed thinking about the fate of a beloved local video store.

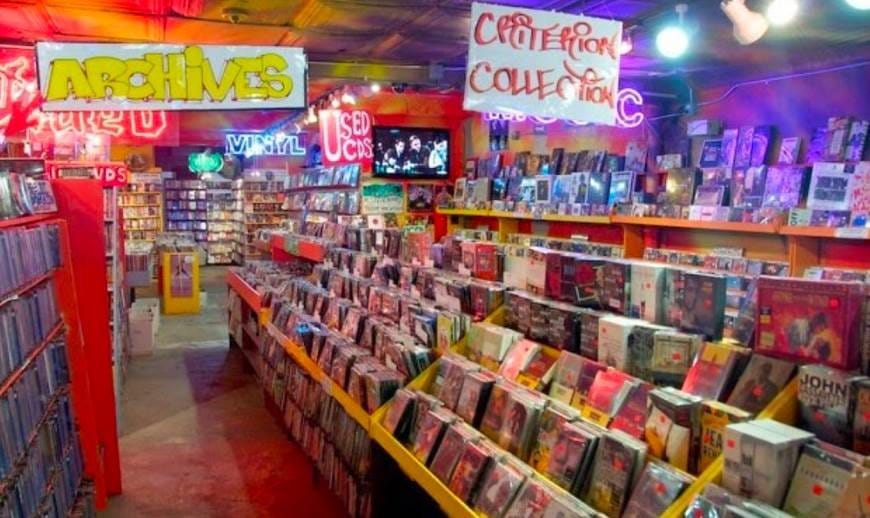

Granted, a certain brand of New York City old head has always been eager to wax rhapsodic (if you let them) about the glory days of Kim’s Video, the mini chain that in its heyday housed 55,000 DVD and VHS titles, many of them rare and/or bootlegged. Former clerks included Alex Ross Perry and Todd Phillips, and customers included the likes of Quentin Tarantino and Chloë Sevigny. The place was long on cool kid cred, to put it mildly.

In spite of its legendary status, Kim’s faced all the streaming-related headwinds you would expect in the late 2000s, and shuttered its last location in 2014. Between 2005 and 2008 the store went from 300,000 members to less than 100,000, the store’s owner Yongman Kim told The Groove.

“When direct streaming came in, almost everyone, myself included, thought, ‘This is too strong a wave, this is it, this is what kills the conventional forms of physical media product,’” he said.

A portion of the original Kim’s Video collection reopened at the Lower Manhattan location of Alamo Drafthouse in 2022, and this time around, rentals are free (though late fees do apply). But what happened in the intervening years is an unexpectedly insane saga — the Sicilian mafia are somehow involved?? — and the subject of Kim’s Video, which is currently screening at Alamo as well as Quad Cinema.

Filmmakers David Redmon and Ashley Sabin kick off the movie some standard-issue “the 90s were better” throat clearing, but things heat up once the movie gets into the nitty gritty of what the hell happened to Kim’s extensive and lovingly curated collection post-store-closure. The short answer? Officials in Salemi, Sicily proposed the town as a new home for the collection, a place where original members could still visit and rent out movies, and where the collection’s new custodians would undertake the onerous process of digitizing the vast collection. Then for a variety of reasons to do with an absurdly corrupt local government — at one point during the documentary, the man who’s been investigating an (alleged) mafia bigwig in Salemi abruptly dies — they let the collection languish and incur damage in a damp, leaking, closed-to-the-public storage space.

It’s all pretty weird, as is the story of the filmmakers staging a pseudo-heist to recover the collection, forcing the town into negotiations that eventually landed some of the collection back in New York.

“One of the conditions of the contract is that no one is responsible for any of the missing movies, that’s kind of nullified,” Redmon told The Groove. (The terms of the exchange also required a seven-day all-expenses visit to New York for Salemi officials — a good grift, you’ve gotta hand it to them.)

“There’s an effort to return to material objects,” Redmon said, noting that he’s seen VCRs jump up in price in recent years. “There was a dematerialization of culture that was rendering any material object obsolete and putting it online as much as possible, including people.”

But getting back into physical media is only really possible if enough people hung onto it during the downswing, and if there are still places open where you can actually rent or buy it. (Old heads in the music space have been saying much the same for years; things don’t just automatically get transferred when new technology rolls around, and as a result, a lot of art is getting lost.) Aside from the ever-reliable New York Public Library and the new Alamo location of Kim’s — located many escalators down in the heart of a mostly-empty mall in the Financial District, not exactly a “neighborhood rental shop” vibe — the city has virtually no in-person movie rental options left standing (other than the X-rated options that also sell poppers).

In the initial advent of the streaming era, individual collectors approached Kim to take their collections of VHS and DVDs off their hands and he turned them down, a move he now regrets. “We all got deceived from the new technology,” he said. “They’d offer me their collections of 2,000 or 3,000 movies and I’d say ‘sorry, no thank you.’ And I don’t know what happened to all those collections.”

There’s a clear lesson here about not panicking in the face of much-hyped new technology — we’re looking at you, AI — and abruptly changing business models before the dust settles. (“We’re seeing these days how regretful [people are] of that kind of wrongful perspective we had,” Kim said. “There were some ways we could have survived, of course at a different size.”)

There’s also a lesson here in not assuming that everything lives forever on the internet, and in taking control of your own personal media library, whether that means amassing downloads or cramming your tiny apartment full of physical media, and maybe even doing a little ad hoc bootlegging.

“I heard from so many people, even other video store owners, who came to Kim’s to rent a movie and made a copy in their own store or house to create their own collections,” Kim said. “Which I didn’t mind at all.”

Comments ()