The new Whitney exhibit that turns city scraps into skyscrapers

From the streets of New York, Louise Nevelson made an art form out of making something out of nothing

It’s Friday night and there’s a line to get into The Whitney Museum of American Art. The institution’s Free Friday Nights initiative is a valiant effort to increase visitorship. In the atrium there’s an acoustic performance that’s captivated a crowd, while pods of people wait for elevators. The fifth floor is abuzz with people who came to see Michelle Obama’s portrait, the crown jewel of the big show on view, “Amy Sherald: American Sublime.” Free Friday Nights seem to be working.

A left turn off the elevator, down a short corridor and a slow right bend, leads to a nook where another exhibition lives. It’s a series of works by someone who’s been called “the grande dame of the art world,” “the queen bee of sculpture” and “the mistress of the marvelous”: artist Louise Nevelson. Nevelson, whose vast body of work spans almost 60 years, is on display in “Collection View: Louise Nevelson.” The exhibited works are a small panoply of the 101 of Nevelson’s works that The Whitney owns.

This exhibit consists mostly of her signature monochromatic assemblage works; made with found objects Nevelson foraged from the streets of New York City. The city was her constant muse.

“I see New York City as a great big sculpture,” she once said.

For Nevelson, New York was her constant compadre, and she was endlessly inspired by it. During World War II, when metal materials weren’t as available, Nevelson found new possibilities with wood. She scoured the streets of New York, collecting wooden pieces in which she often saw interesting shapes, figures, and faces; they spoke to her. She began an intense career-long dialogue with wood as her primary material, giving a banister railing or chair leg a second life, as she described in a 1977 documentary. From the streets of New York, Nevelson made an art form out of making something out of nothing.

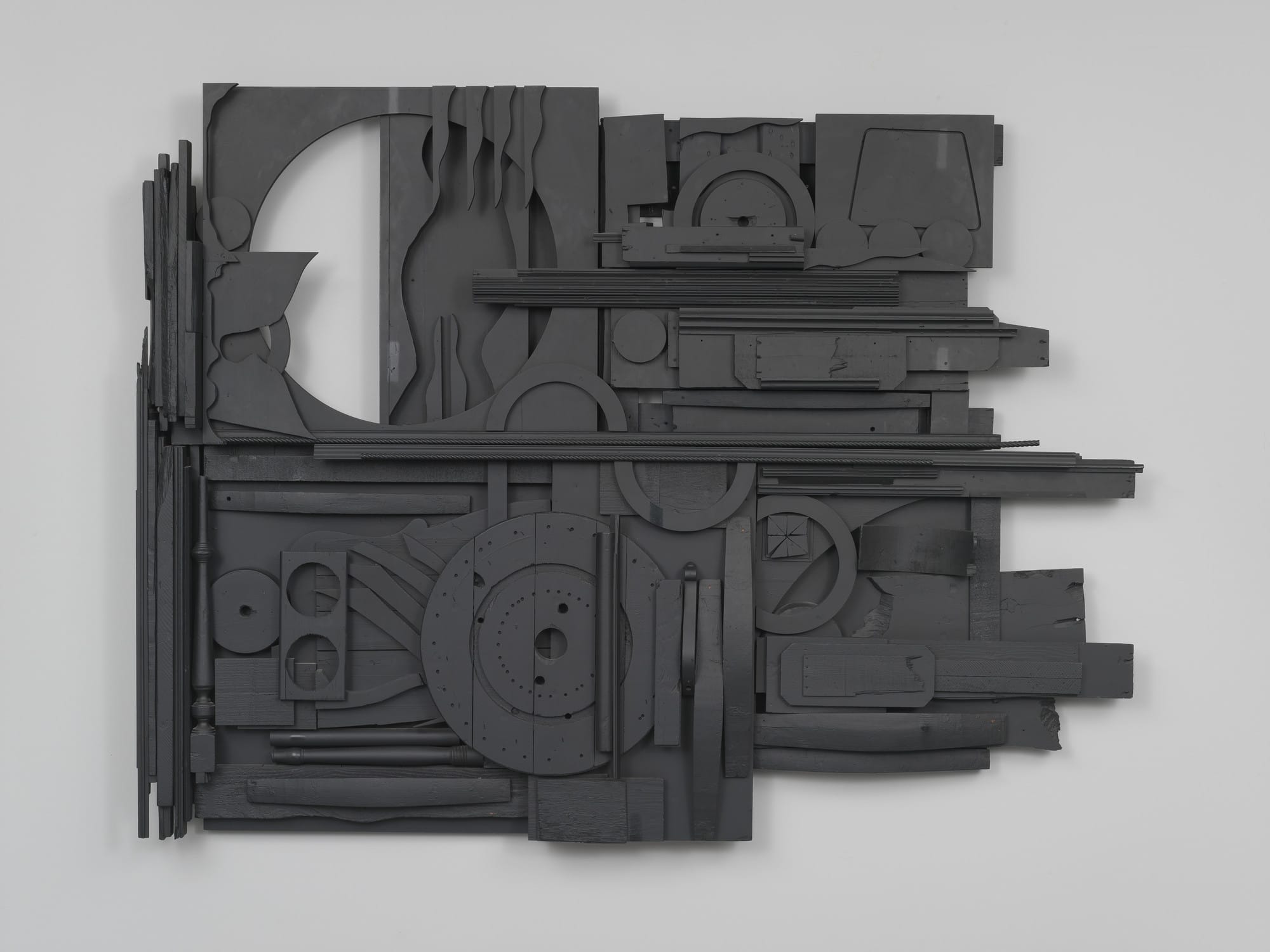

In one of the artworks, Moon Gardenscape No. XIV (1969-1977), Nevelson creates a 2-D sculpture, a melange of small objects composed in Nevelson’s aesthetic. A circle cutout adjacent to cylindrical bits looks like a record player. In conjunction, the edgings peak and valley like skyscrapers amidst the city’s horizon. Later in her career she designed the chapel of St. Peter's Lutheran Church in Midtown and Sky Gate, New York a 17-foot by 32-foot flat sculpture that was located in the mezzanine of the North Tower of the World Trade Center and was destroyed in the September 11 attacks.

Louise Nevelson was born Leah Berliawsky in 1899 in Pereiaslav, which is in today’s Ukraine, but back then was part of the Russian Empire. At the turn of the 20th century, Louise and her family emigrated to Rockland, Maine. The family's assimilation into American life was met with challenges as Nevelson’s father struggled to establish a lumberjack business and the family faced persistent antisemitism. Her father’s work as a lumber merchant made wood a consistent presence in her home, foreshadowing the long relationship she would later have with the material.

Nevelson began dabbling in art in high school, but it was ultimately her dissatisfaction with her family’s financial standing, language differences, and struggle against local religious biases that led her, like so many eccentric characters before her, to move to New York City in 1920. After becoming a mother and separating from her husband, Nevelson answered art’s insistent call. She abandoned the bourgeoisie society lady dream her husband had for her and opted to pursue MFA. She studied in Europe with the renowned abstract painter Hans Hofmanns, assisted Diego Rivera on his iconic mural Man at the Crossroads at Rockefeller Plaza (she also had a romance with him) and attended the distinguished Art Students League in New York City.

Nevelson experimented with various media, but by the 1940s she began the sculptural phase of her practice. She was in rare form as a woman working in what was thought of as a very masculine discipline.

In that 1977 documentary, she recounts sitting at a coffee counter on Sixth Avenue that was popular with artists at the time, where a bunch of men were talking about art.

“One of them said to me, ‘don’t you know Nevelson? You’ve got to have balls to be a sculptor,’” she recounted. “And I said, ‘Oh I’ve got balls.’ And they shut up. So I had confidence.”

She worked with unconventional materials, shapes and colors and was so grounded in her lens on the world — herself, New York and her work — that she was able to forge a new path. She shone in group exhibitions, most notably Exhibition by 31 Women curated by self-proclaimed “art addict” Peggy Guggenheim, who is also known for saving thousands of art works from the Nazis. The show opened in January of 1943 is believed to be the first U.S. exhibition dedicated solely to female artists. Nevelson was joined by Italian surrealist Leonor Fini, painter and writer Meraud Guinness Guevara and her frenemy Frida Kahlo.

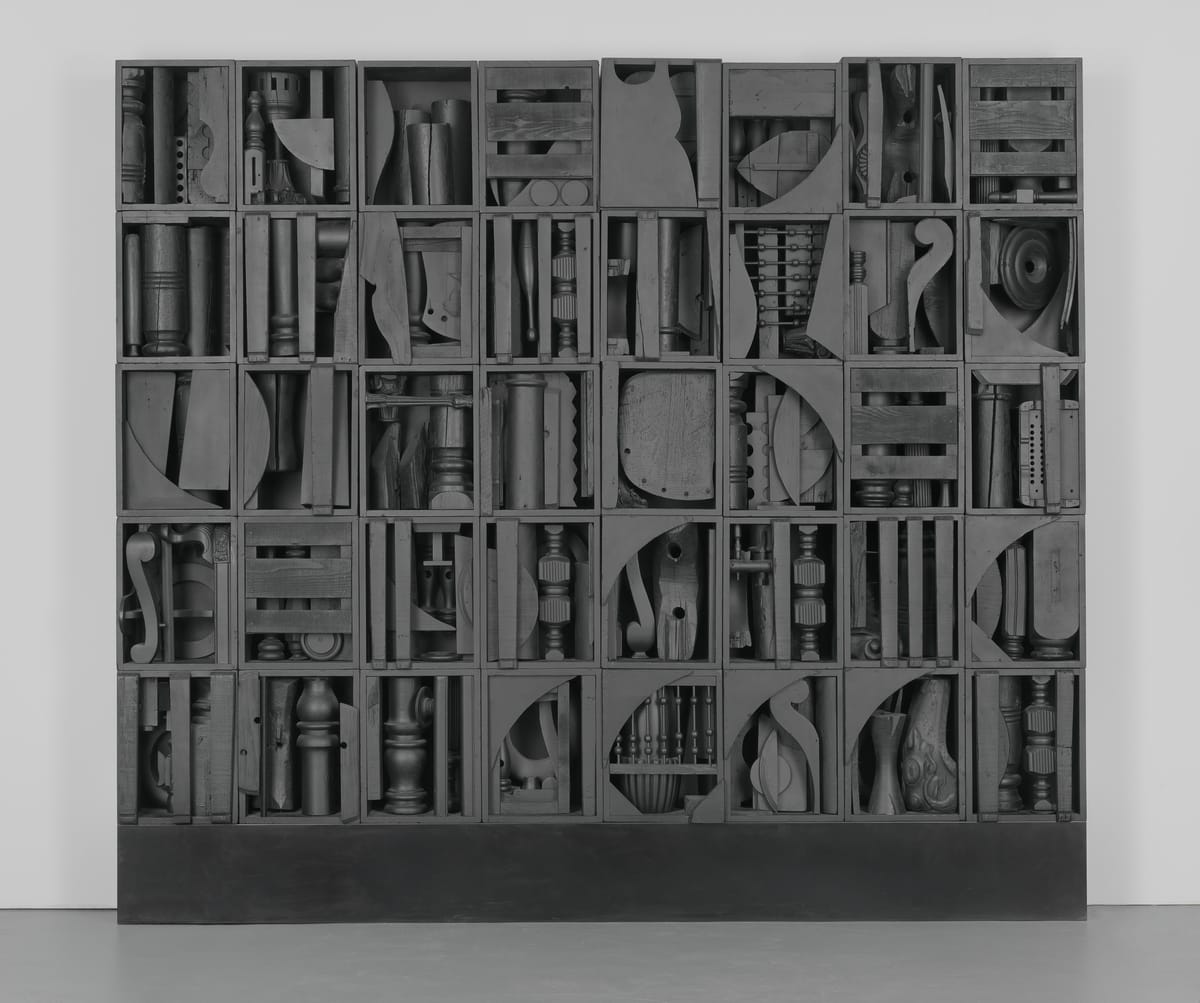

Against the wall in the Whitney exhibit are 40 hollow squares, stacked five squares high and eight squares wide, each square is about three inches deep. All of them filled with ornate bed posts, antique chair legs, picture frames, banister railings and fragments of finials, all wooden, all painted black. The artwork, Nevelson’s Black Chord (1964), is symphonic, its scavenged pieces are the orchestra’s various instruments, and Nevelson the maestra masterfully composing the elements to make a cohesive opus. The found objects are all different and yet all in concert with one another, and the harmony among them is palpable.

The layout of the Whitney’s exhibition speaks to Nevelson’s concept of “environmental art.”

“I started that word because everywhere I am I like a certain kind of order. I use my eyes and project a whole environment,” she explained while being interviewed on About the Arts, a TV program in 1978.

By the 1950s, Nevelson honed her practice. She broadened her color palette to include white and gold, and later expanded her materials beyond wood to plexiglas, and cor-ten steel. She made her first museum sale to The Whitney in 1962 and that year she was also selected to represent the U.S. pavilion at the Venice Biennale. By the 1970s, Nevelson garnered large commissions all throughout New York City.

A hallmark touchpoint of her “empire,” as she referred to it, was the Louise Nevelson Plaza. A massive public art installation in lower Manhattan that sits at the intersection of Maiden Lane, Liberty Street and William Street, adjacent to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Nevelson created an outdoor environment that displayed seven large-scale metal abstract sculptures, accompanied by seating and flora. In 1978, the Louise Nevelson Plaza was the city's first public space named after and designed by a living artist. The original design remained until changes were made to the park to increase security after 2001’s September 11 attacks, and today a revised design with Nevelson’s seven original works lives on.

Nevelson’s artistic process was irrevocably linked to her personal constitution, to claim her own life. “If I’m on earth, who do I owe myself to?” she inquired, only to respond confidently, “To myself.”

She had a very clear sense of self, in spite of the expectations placed on women of her generation, she trusted her intuition to light her path forward. Often led by instinct, she was steadfast about bringing her ideas and visions to life, always honoring her point of view first and foremost. Though women living on their own terms is common today, Nevelson was in rare form in the 1950s, 60s and 70s when her career was in full bloom. The expectation then was for women to revolve around their families; a woman's ambitions were on the periphery, if considered at all. Nevelson ferociously forged ahead on her path, coupled with pioneering into the male-dominated world of contemporary art, particularly as a sculptor, and garnered success.

Nevelson’s decades-long love affair with New York City was her constant muse, ever-present in all her work. She also claimed the city as her own, and her work continues to live all throughout New York. She achieved what many artists can only dream of: having a formidable place in the contemporary art canon, being embraced by a variety of collectors, private individuals and public institutions, and leaving behind a legacy that continues to captivate and inspire New Yorkers.

Collection View: Louise Nevelson at The Whitney Museum of American Art is on view until Aug. 10.

Comments ()