What is participatory budgeting, and can it really fix life or death issues?

You can submit your ideas for community improvement projects now, but some wish it didn't have to come to this.

By Tim Donnelly

Dinu Ahmed had been walking through her basement in September 2021 just moments before she heard the boom resounding from the downstairs of her East Elmhurst home. She checked the basement again and saw rain and sewage overflow from remnants of Hurricane Ida were now pouring down her basement steps. The boom, she realized, was the sound of the basement door being ripped off from the sheer force of water.

The storm would dump five feet of water and sludge in the basement of the home her family has lived in since 2002. She’d eventually have to gut the entire thing and lay out $12,000 just for cleanup.

“Had I been down there, I felt it would have been a certain death trap,” she told The Groove this week.

Fast forward to the morning of September 29 this year when heavy rain was pounding the city again, Mayor Eric Adams was nowhere to be found and Ahmed was getting ready to go to work as a lawyer for immigrant children. Then she saw the basement toilet, and the sewage water backing up through it. She decided to act fast this time: with water pouring into her basement again, flooding her home office space, she tried to save her computer monitor. She felt a tingle in her hand, and quickly realized she was being electrocuted while trying to disconnect it from the power strip. The flooding was scary, but predictable.

“How is it, two years later, we feel like we’re in precisely the same spot we were in when Ida happened?” she said.

Ahmed has been on a campaign to flood the inbox of every elected official she can contact since that first incident two years ago, from her community board up to Congress. The storm in 2021 led to 11 deaths citywide, and President Joe Biden toured East Elmhurst’s damage at the time, but so far nothing has changed.

“It's just like an untenable situation. Our lives are literally at risk,” Ahmed said. “Having the president come down here, having multiple fatalities, nothing seems to have moved the needle in terms of the structural improvements we need to feel safe.”

Now even on regular rainy days, she and her neighbors nervously eye the street outside the windows to look for flooding, feeling frustrated, powerless and overlooked.

Her struggle led her to a Hail Mary attempt at change this month: she submitted her idea for a sewer system overhaul to this year’s Participatory Budgeting cycle. The funding program is an annual chance for residents in participating City Council districts to nominate, develop and vote on which improvements are needed in their neighborhoods. Each district gets $1 million to spend on infrastructure projects, and those projects usually run a wide gamut, from water fountains at playgrounds to new tech for public schools.

“People here in this neighborhood shouldn’t have to jump through so many hoops."

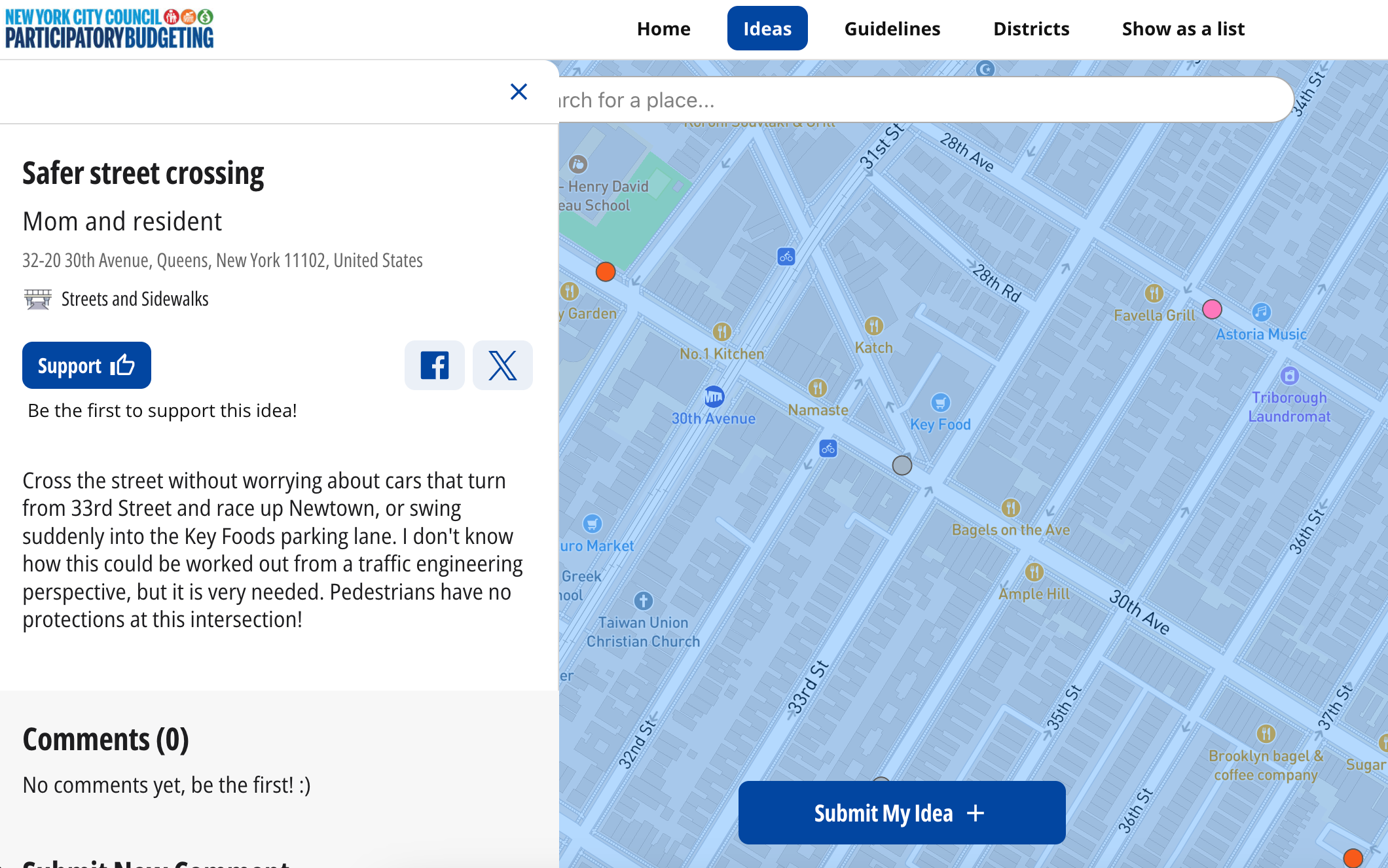

All this can sound like a bit of wonky local civics, and it’s not widely popular in some parts of the city: the projects are sometimes decided by a few hundred votes. But for some it has become a hope-and-a-dream forum to ask for long-overdue health and safety upgrades in their neighborhood, things like sewer upgrades, street repairs, food distribution vans and safer pedestrian crossings.

The program is billed as a quaint way to engage everyday New Yorkers in direct democracy and fixing their communities. But in some cases — like Ahmed’s — it can feel like Hunger Games-style fight for resources with your immediate neighbors over basic, life-saving needs.

“I don’t understand why the burden of doing this work of collecting this information is being passed on to the people who are trying to recuperate from this and keep themselves safe,” Ahmed said. “We’re going to do what we have to do in order to be heard, take this to every venue. Does it have to be this hard?”

What is participatory budgeting?

Some days you walk around your neighborhood and think things like “a bench should be here,” “all this trash shouldn’t be here,” “man I wished this water fountain worked” or “all these dogs attacking me sure could benefit from a new dog park.” Participatory budgeting is for those kinds of citizen-driven ideas to improve the city.

The program began with four council districts in 2011 and expanded over the years, with 29 districts participating this cycle. Each participating City Council member earmarks at least $1 million each year for the process. Volunteers meet to figure out which pitches are most feasible and needed, and turn them into full proposals. Then, people in each district get to vote on the projects, and the winners become reality.

And as of last year, there are now two participatory budget processes in the city. The mayor’s office launched its first citywide version of it last year, with $5 million spent to fund 46 projects.

Both versions of this are in the ideas collection stage right now, which means that you still have time to pitch your big ideas.

How do I submit an idea?

The City Council version is for projects that cost at least $50,000 and have a lifespan of at least five years. You can submit ideas through November and don’t need much homework to submit one either: the form just asks for the name of the project and a brief description of how it will benefit the community. Volunteers and community delegates turn some of the ideas into full proposals, and the district gets to vote on their favorites during a nine-day period in April and May. Submit one here.

The mayor’s version — known as The People’s Money, with an emblem that unfortunately resembles a lottery logo — is not for construction projects. It’s used for programming such as events, fairs, workshops, trainings and classes; expanding or enhancing direct or social services like after-school programming; community organizing campaigns and research studies. Public improvement projects worth more than $50,000 are not suitable for the fund, according to the mayor’s office. You can submit ideas through Nov. 19. Voting will happen in April and May. Submit one here.

What kind of ideas actually get picked?

Much of the successful projects in years past are bread-and-butter civics stuff, related to schools, public safety, street trees, playgrounds and public housing. In previous years, for instance, the project funded a water hookup for the Red Hook Community Farm ($500,000), bus countdown clocks in Queens ($200,000), NYPD security cameras in Brownsville ($141,000) and new water fountains at nine East Harlem schools ($360,000).

Like most city elections, turnout is abysmal here too. Many of the winning projects are decided by 1,000 votes, but some win with 300 or fewer.

You can see a list of past City Council funded projects here, and the mayor’s version here.

What are people proposing this year?

Anyone can submit an idea right now so this year’s proposals range from deadly serious — like Ahmed’s — while others can feel like not much more than some churlish trolling.

One New Yorker has proposed a “modest and respectful” visitor center on Hart Island, the mass grave site set to open to the public for the first time later this year. Another person in Cobble Hill requested funding for a dedicated person in charge of coordinating refugee services in the community.

In Manhattan, one person requested Citi Bike e-tricycles to improve accessibility. Another Manhattanite pitched “Cleaning up homeless and not coming back,” another just wrote “ban cars.” One person in Queens wants to use the money to soundproof Forest Hills Stadium, an issue that’s in the news this week. This year’s map of requests — which you can peruse here — includes lots of dog parks and pickleball courts.

Wait, shouldn’t the city actually be paying for all of this stuff anyway?

Well now there’s an interesting question. An extra dog park or street tree here or there makes sense as a community driven request. Stopping toxic wastewater from entering your home during rainstorms or renovating school bathrooms seem like they are the responsibility of someone with a higher pay grade than the ordinary citizen.

Ahmed heard about participatory budgeting through her council member’s newsletter. She wasn’t familiar with the process but wanted to leave no stone unturned in her efforts.

“People here in this neighborhood shouldn’t have to jump through so many hoops,” she said. “It should not be that we have to go through so much to get the attention of the people who work for us.”

Plenty of council members opt out of the program. All of Southern Brooklyn, the Rockaways, parts of eastern Queens, Midtown and the Bronx are not taking part this year, according to the map. In the past, some council members have considered the process an unnecessary layer of bureaucracy.

"Participatory budgeting takes an extraordinary amount of office time and resources for no discernible improvement in outcomes over working through the existing vast civic infrastructure for public participation,” former Queens Council Member Rory Lancman replied when Gotham Gazette tried to get to the bottom of why some districts didn't participate in 2015. “My district does not lack for opportunities and vehicles for community engagement, which I'm proud to say my constituents take ample advantage of."

Research shows the process does actually change spending priorities in the city. After participatory budgeting was adopted, more money went to schools, streets and public housing; less went to parks, housing preservation and development, according to a 2020 study by NYU.

“The next step, now, is to better understand if and how these shifts in spending priorities represent more equitable spending, as is the ultimate goal of PB," Erin Godfrey, one of the study's authors, wrote.

Some of the people submitting ideas this year seem like Ahmed, people frustrated by lack of official action on key issues, and taking matters into their own hands. At least a few that I reviewed were submitted by teachers or principals at public schools, asking for air conditioning for class rooms, library renovations and more learning areas.

Who decides what projects even get voted on?

It could be you, fair citizen. In fact, anyone 11 years or older who lives, works or attends school in the district is eligible to become a budget delegate. Delegates meet this fall and winter and determine feasibility of the pitches and develop some of them into full proposals to go on the ballot. You can get involved in the mayor's version too.

You can also volunteer to become a poll worker to help beat the streets to get votes in the spring.

Lobbying to drum up votes for your own project can be part of the process. That’s something Ahmed is already familiar with after going door to door in her neighborhood and handing out flyers to get the sewer and flooding issue addressed. It’s been “mentally grueling,” she said, but she feels like she has no choice but to keep trying.

“There’s a lot of the political processes in the city that feel really obscure to me,” she said. “If there is another fatality, there is not one elected who represents this area who can profess to be ignorant about what’s happening here.”

Caption details and the amount of money Ahmed spent cleaning up her home in this article have been corrected.

Comments ()