Why is New York City failing at composting?

Mandatory composting begins April 1, but participation is still abysmal

When curbside composting came to Brooklyn in 2023, many people, including me, heralded it as the end of a long, smelly nightmare of lugging my food scraps around the neighborhood to deposit in a neighborhood drop-off site, suffering the occasional sluice of mystery juice running down my leg. Not everyone felt this way, apparently.

Collection rates for organic waste have been abysmal so far, putting the city a long way from reaching its climate goals for the program — not to mention the side goals of rat-starvation and smell-eradication. I know of two Brooklyn men who exemplify this in the extreme: both of them, separately, upon receiving their free brown food scraps bin from the city, were so furious at the very concept that they immediately tried to throw it out. One tried unsuccessfully several times to put it out for trash collection; the other, realizing Sanitation would not take it so easily, took a saw and cut it into pieces to feed it into the trash. It’s a level of mad at an inanimate object that’s impressive, to be honest (the latter said he later regretted the decision).

In April, the city is going to start issuing fines for landlords and property owners who don’t properly separate organic materials from trash; but the methods that have worked elsewhere to improve collection rates might not work here.

Embracing curbside food scrap collection seems like an easy win for a city that ostensibly wants to be a leader in fighting climate change, as organic waste rotting in landfills produces methane, a potent greenhouse gas. At the very least, it would seem an easy way to fight rats who feast on food scraps in garbage and the famous smells that percolate up from big black trash bags left on the street.

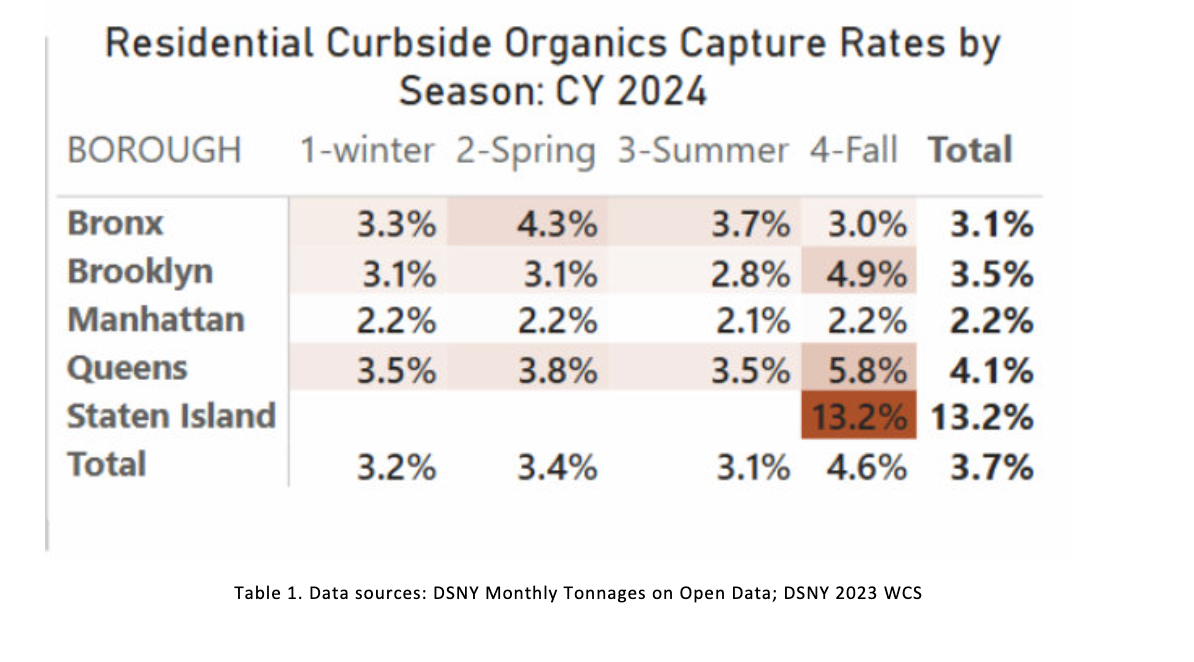

But that seems to not be the case: Only 4.6 percent of all organic waste in the city was separated and collected in the fall, when collection was available city wide, according to a study by a Baruch College professor that Gothamist reported on this month. Staten Island, contrary to everyone’s hack jokes about it, was ahead of everyone with 13.2 percent of food waste being saved from a landfill; Queens was in second place with a still-paltry 5.8 percent.

“That's not just, ‘Oh, it's a start.’ That is abysmal,” Baruch School of Public and International Affairs professor Samantha MacBride, who conducted the study, told Gothamist.

Meanwhile, we’re getting lapped by the Left Coast loonies in San Francisco, where mandatory composting has been in place since 2009. The city has been successful in diverting 80 percent of its waste from landfills, through composting and recycling. Sure, New Yorkers weirdly identify with our trash piles, but shouldn’t the concept of being worse at something than San Francisco motivate us to try harder?

Well, we’re going to have to get better at it soon. As mentioned above, separating organic waste from other trash becomes mandatory starting April 1, and the Department of Sanitation can start issuing fines between $100 to $300, depending on the size of the building, to landlords who don’t comply.

Part of the problem with the city’s curbside collection program is that calling it “composting” is a misnomer. The food scraps collected at the brown bins and in the Bluetooth smart bins on street corners are not actually becoming compost; they get churned into biogas, a heating source that still produces methane. It’s a better use of the waste than rotting in a landfill, but it does not evoke the crunchy, back-to-earth spirit of compositing.

The city has also gone all-in on the biogas route, and eliminated funding for the so-called community composting sites last year, the collections at places like the Grand Army Plaza farmer's market that actually turned your food back into compost that could be used for soil. With the extremely low collection rates in mind, the City Council this week allotted funding to reopen two community composting sites at McCarren Park in Brooklyn on Saturdays and the Forest Hills farmers market in Queens on Sundays. Other community composting groups are fighting for their lives, saying that curbside collection will never be enough.

“When I think about all of the different things we pay for to divert waste and it’s still not enough to get rid of all the food waste from New York City, it gets me thinking: we can’t just rely on this system. It has to be more,” Nando Rodriguez, head of Brotherhood Sister Sol, a Harlem-based non-profit, told City Limits.

Part of the problem, some compost advocates say, is education. With budget cuts last year, which Mayor Eric Adams attributed to the migrant crisis, the city’s outreach about how and what to compost has struggled to reach all New Yorkers. One observer called the program “invisible.” (I’m reminded of a brief attempt at a composting program at Citi Field pre-COVID, where compost bins were set next to regular trash and recycling bins, but without much signage or education about what went into them or why. Every time I looked in one, they were just full of beer cans and regular trash. The stadium eventually got rid of them).

Residential composting programs took time to be successful in California, and education was a key part of it. But that kind of education might not work in New York City.

Nick Lapis, director of advocacy for the nonprofit Californians Against Waste, told environmental news site Canary Media that cities should talk about their composting bins not as a matter of complying with mandatory regulations, but instead to “talk about the soil and how we’re using it to grow food, which then kind of explains to people why they need to keep plastic out of the bin.”

That back-to-mother earth angle doesn’t work quite as well when you’re using curbside food scraps to turn into biogas; an image of the digester eggs at Newtown Creek spitting out methane — while sometimes romantic — is not exactly a Captain Planet recruitment pitch.

New Yorkers are understandably frustrated at the turn in the composting program; the city has a history of environmental mandates that seem like good ideas in practice, but lack the muscular enforcement and education that would infuse them into the city’s DNA (like the city’s plastic bag “ban”). Mayor Adams is accused of committing many bribery and corruption crimes, and is now in the pocket of a president who certainly doesn’t give a shit about composting. But before all that, he was on track to be known as the mayor who finally actually did something about the city’s addiction to giant piles of stinky black trash bags on every street. Businesses and residential buildings now have to containerize their trash, a huge leap into the 19th century that the city struggled for decades to wrap its head around.

The city has the ambitious goal of sending zero waste to a landfill by 2030; halfway through the decade already, that seems incredibly idealistic. But as spring approaches, I implore you to consider this: separating your food scraps from your regular trash — and storing them in an airtight container in your freezers — is at least a way to control the bugs that flock to your kitchen when the weather gets warm, and it’s a way to eliminate the hyperlocal hot trash smell from your own home. And if we can at least get to zero hot trash smells by 2030, that’s progress.

Comments ()