Can you afford to die in New York City?

Being dead won’t save you from the city’s housing crisis

It costs a lot to live in this city. It costs a lot to die here too.

The price of a funeral — burial, box and plot of land, not including headstone — can run between $4,000 to $20,000 in New York City, according to industry estimates. Those numbers have been rising in recent years. Getting cremated can run between $500 to $3,5000. It might be the final rent you’ll ever pay, but it’s becoming a burden, and the city is trying to do something about it.

The city government offers financial help to cover funeral services for anyone who can’t afford it, but officials say it doesn't go far enough, and some local lawmakers are making moves to change it this week. That’s not even mentioning that the funeral industry is pockmarked with fraud and companies taking advantage of grieving loved ones; the city last year settled a lawsuit with one Bronx-based funeral home, which agreed to pay more than $600,000 in restitution for deceptive business practices.

The city’s Human Resources Administration Office of Burial Services can provide up to $1,700 for funeral or cremation services for low-income city residents, but there’s a catch: if the total cost of the funeral runs over $3,400, the city can’t help at all. You won’t even get a fraction of the money, and that’s become a problem as funeral prices rise.

“The reason for rejections and denials, this is the most common, due to the cap,” a representative from City Council Member Farah Louis’s office told The Groove.

Louis, who represents the area of Flatbush, Midwood, Canarsie and Kensington, introduced a resolution earlier this year to try to increase the cap to allow the city to provide financial help for more funerals. The cap comes from a state law, her office said, so the resolution calls on the state to raise the cap from $3,400 to $6,000, which frees the city up to help with today’s rising funeral costs. The resolution will go before the Council's Committee on General Welfare and the Committee on Health today (Oct. 16); with hopes that the full Council will take up the resolution and pass it along to the state soon.

The cap, Louis’ resolution pointed out, disproportionately affects low-income New Yorkers, especially those with cultural customs whose need for specific burial practices often quickly exceed the limit. It leads to what one researcher called “funeral poverty.”

The impetus to raise the cap comes from a real case involving one of Louis’ constituents, a tragic death at the West Indian Day Parade, and a community grieving together. Denzel Chan, a 25-year-old Flatbush resident, was shot and killed on Eastern Parkway during the parade in 2024. His family couldn’t afford funeral costs, so local officials stepped in to try to help. But their application for HRA funds was denied, because the overall cost was too high.

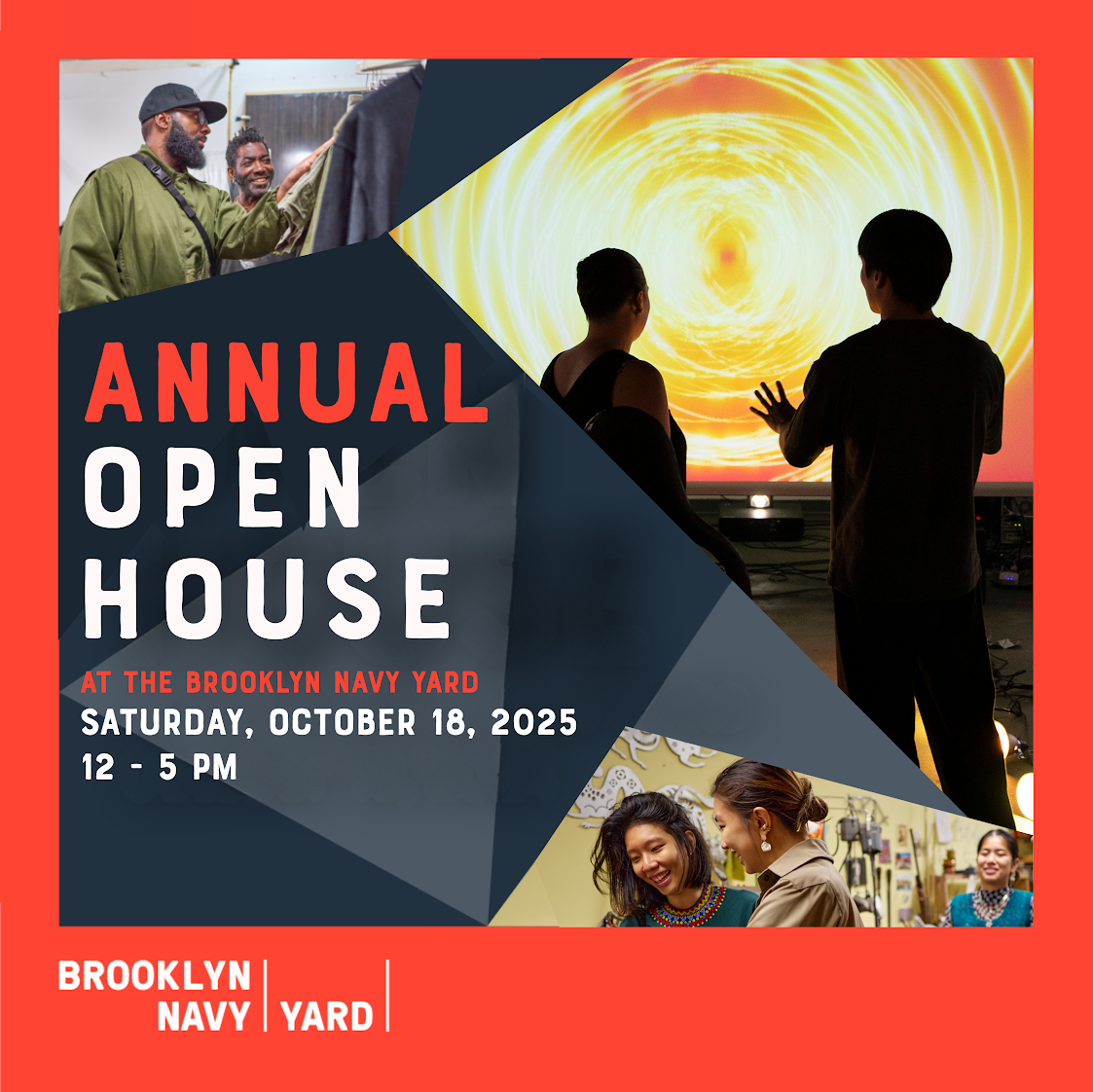

Sponsored: Join the Brooklyn Navy Yard for their Annual Open House on Saturday, October 18— a free celebration of makers, creativity, and community. Visit the Yard from 12-5 PM and get behind-the-scenes access to over 35 trailblazing Brooklyn-based businesses in fashion, design, technology, and more. Participate in hands-on demos, exclusive tours, timed programs and enjoy on-site food trucks and live entertainment all in one dynamic space! RSVP here.

Local officials and family members were able to eventually crowdfund money for a funeral. Obtaining a burial plot, funeral home venue, embalming for a viewing, obtaining a death certificate and other fees all add up quickly (GoFundMe has a dedicated page for understanding funeral costs, to give you a sense of how often people turn to crowdfunding).

The reasoning of why the cap is set at $3,400 cap has always been unclear, officials said. Like nearly every other expense, funeral costs, with casket and burial, have gone up 5.8% over the past two years, with cremation increasing 8.1%over the past two years, according to the resolution. That’s actually not as much as the rate of inflation over that time, but it’s still a burden on top of already high costs.

“We should never put the family in this position,” the rep from Louis’s office said.

Nickel and diming the dead

How much should it cost to be dead in New York City? Should it cost anything?

Like anything, it comes down to real estate. A grave site in celebrity-filled Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn —a plot big enough for you and two guests of your choice — can run $21,000 to $30,000. Less in-demand real estate at Resurrection Cemetery on Staten Island starts at $4,000 for a simple flush grave marker, plus another $2,000 - $3,000 to dig and fill the grave itself.

SUPPORT US: Weird time to ask for money we know but The Groove is entirely run by living journalists and almost entirely funded by our members.

Join us for as little as $6 a month to unlock bonus content, perks and more!

The prospect of dealing with post-mortem housing costs can be enough to make your bones rattle in frustration. You’re dead, free of the world and its service fees and rate hikes and $20 burritos, and still someone will be out there price comparison shopping to figure out what to do with you.

Me, if I had to choose, I’d elect death in the most natural way: shot out of my seat at the top of the Cyclone, spiraling in a death dive into one awaiting pile of compost, where I will be consumed, gradually, back into the Earth, no need for a box or crematorium or tombstone (as tempted as I would be to get a fun Old West Halloween tombstone)l just visit me in the grass or whatever grows from the mound where I landed, and don’t let them shut down the Cyclone over it either.

I might be able to do that soon: New York state legalized composting human bodies in 2023, but it is still working out the regulatory kinks on that. It’s legal in New Jersey now, but I’d rather die than be buried in that state.

But even slowly turning into moss isn’t cheap: one New Yorker told news organization The City she spent $8,700 to ship her partner’s body out of state and have it composted. It’s more expensive than cremation but much less than a burial; families can take the compost home at the end, which looks like regular organic material compost and makes enough to fill the back of a flatbed truck.

“Tons of people have taken little bits of him, so it pulled people together to do fun things with his body in a way that burial and cremation can’t,” a family member told The City. “I have one friend who put him in her house on a money tree. Money didn’t have much of a meaning to him, but he really loved puns, so the fact that he’s a money tree houseplant makes me smile.”

Even with greener, more palatable options emerging, why does it cost so much just to not exist any more?

The mass grave option

The fallback, free option for all New Yorkers — one some even opt for voluntarily — is to be sent to the city’s mass grave on Hart Island.

The tiny slip of land off the coast of the Bronx is a mostly featureless field, broken up only with a few building relics, clerical markers and divots in the grass where fresh holes were filled. It’s served as the city’s burial ground since 1869, home to the bodies of the unclaimed or anyone too poor to afford other arrangements. It houses more than 1 million people, including mass quantities of deaths from Covid and AIDS, making it most likely the largest burial site for AIDS deaths in the country.

The site opened to public visitors in 2023, with free tours anyone can attend via lottery, though some advocates say the tours aren't enough, and gloss over the history of the island (read our report from a visit to the island here).

But even the city’s mass burial site might be running out of room. In recent years, the city increased the number of bodies in each mass grave site, with up to 200 caskets in each trench, an increase of 50 caskets from the standard, according to The City, the news organization. A 2022 study suggested the island could run out of space by 2030. The City Council is also trying to get more info on this this week: another committee hearing today will talk about a proposal to require the city to study the island further, including looking at available burial locations and estimate the remaining burial capacity.

As inaccessible as it is currently, there is something morbidly romantic about being interred forever among the city’s unclaimed masses, one final packed living arrangement that — much like living in the city itself — is actually more environmentally friendly than other options. The lump of land around you will likely one day become public park land, and your bones will melt into a part of city history, trod upon by families and macabre tourists alike, forgotten but always somehow remembered as part of the whole.

The Hart Island Project, which helps map the island and advocates for increased access, wants the city to consider more green burials on the land, using biodegradable coffins and fewer embalming chemicals. The group wants the city to reuse land too, pushing aside decomposed bodies to make room for new ones. Like moving swiftly through a subway turnstile or bagel shop line, anyone buried on Hart Island can take some pride that you're not taking up too much space in the city, quickly making room for the endless line of people coming after you.

If you end up there, who knows who your neighbors might be, but with burial prices this high, you can’t beat the rent.

Comments ()