POPS can be the cure for winter cabin fever — if they're open

Privately owned public spaces are everywhere, but how public they actually are varies wildly

We’re in the final (and worst) stretch of winter: the usual haunts are worn out, we’ve survived the longest deep freeze in 65 years and the long promised thaw is mostly just revealing more dog shit. At the same time, truly accessible, welcoming, and free places to simply exist in public are harder to come by. Privately Owned Public Spaces, or POPS (which also date back 65 years) were meant to help fill that gap. In theory, they’re a public good but in practice, they’re restricted.

"These places are designed not to be used!” Miles Grant, founder of the group FreePOPS, which advocates for more usage of the spaces, told The Groove. “But that's what makes it so satisfying to see them used in a human way.”

He recounted once seeing “two very scraggly looking men” having a philosophical debate in the lobby of a POPS at NBA headquarters on Fifth Avenue.

“That's definitely not what the NBA wanted and yet it was completely legal and there was nothing they could do about it,” he said.

What follows is a quick history of POPS, some challenges, and where to find the ones that might help with cabin fever.

What Is a POPS?

POPS, as defined by the New York City government, are privately owned public areas "dedicated for public use and enjoyment," though that dedication is often questionable. POPS include plazas, arcades, atriums, indoor public rooms and other spaces embedded in or adjacent to private buildings.

This year marks 65 years since the 1961 zoning law that guaranteed developers larger buildings in exchange for making space, light and air available to the public, a trade that reshaped both New York City and cities elsewhere. To get more specific, public space is generally defined as a place that is open and accessible to the general public, though the accessibility of a sidewalk is clearly different from that of a park, plaza or indoor atrium.

Another way to think about it is simpler and more human: “where do we take our communalness, our publicness?" We ourselves are the public, where are we actually allowed to gather?

👋 Hi! If you can see this, we know you're not a member of The Groove yet. We rely solely on member contributions to keep this work going. Join us today for as little as $6 a month and you'll unlock sick perks too.

Public space is a necessary human tradition. From ancient markets and forums to modern parks, public spaces have long promoted community life and social trust. People have gathered, socialized, shopped, rested, debated and experienced chance encounters in public space for all of civilization. Historically, these spaces are where cities have practiced democracy.

Public space is essential urban infrastructure for civic life, and in a moment where the barrier to entry for a seat is a $7 latte, it feels very necessary.

Public space, with conditions

In New York City, there are nearly 600 POPS you should, in theory, be able to take advantage of.

Most of them concentrated in Midtown Manhattan and the Financial District, where the tallest skyscrapers congregate. Together, they cover more than 3.8 million square feet of space, though only three are located in Brooklyn and a single one in Queens. The city points out that the spaces are equivalent to nine Bryant Parks or Union Square. That’s roughly 350 Olympic swimming pools or about 90 football fields’ worth of space. On paper, that’s an enormous amount of public life but access to it often hinges on questions of rights.

Occupy Wall Street both relied on a POPS, and helped popularize them. The protest began in September 2011 at Zuccotti Park, a space that was technically private property but legally required to be open to the public 24 hours a day. Because of its POPS status, police could not immediately force protesters to leave without the consent of the property owner, who declined to do so for weeks, allowing the encampment to grow into a two-month long protest. (Fun fact: Zuccotti Park was formerly named Liberty Plaza, a much more relevant name, once the protest asked questions of the legal gray zone around privately owned public spaces.)

“In future years, people will remember 2011 as the year in which physical public space reclaimed its lofty status in the public sphere thanks to the audacious actions of engaged individuals,” Jerold S. Kayden wrote in the Architect’s Newspaper in 2011. Hybrid spaces like this now exist in cities around the world, including Auckland, San Francisco, Dublin, Seattle, Seoul, Toronto, and many others.

As POPS have proliferated in cities, so has a fundamental tension: the boundary between private ownership and public access, and who gets to define it. It’s part of both the possibility and tension of urban living. Cities are for and by people, and people also come with a variety of behaviors that lie on the spectrum of social acceptability. We live in a society; how do we maintain it?

Urban life depends on the idea that public space should be open to all, even as everyday behavior on those spaces (like resting, gathering or sometimes just sitting) gets policed or restricted depending on privately written rules. That tension was laid bare in London in 2011, when Occupy London activists attempted to occupy Paternoster Square, a historic site, but also a privately owned plaza meant to be “public,” only to have a court ban protesters.

The POPS at Trump Tower has also been a site for this tension. It was fined for replacing a required public bench with a political merchandise kiosk (amongst other violations), also partially in response to protests. Today the question of rights in these hybrid spaces persists: a Brooklyn man and retired prosecutor is suing New York City for First Amendment protections after being arrested while protesting in a POPS.

Other, more simple challenges

It’s not just rights that are contested in POPS; it’s also basic usability. Reports from the City Comptroller’s Office in 2017 and the New York Times in 2023 found that nearly half of New York City’s POPS failed to meet the basic guidelines intended to make them usable as public space.

A POPS scholar recently found that because they’re privately managed, POPS are regulated in ways that limit how the technically public space should be used. They discourage spontaneous use, certain bodies or activities, and prioritize control over true accessibility. In many cases, developers use active management strategies (like security presence, hostile design that deters lingering or rules that restrict expression) to manage who uses a POPS.

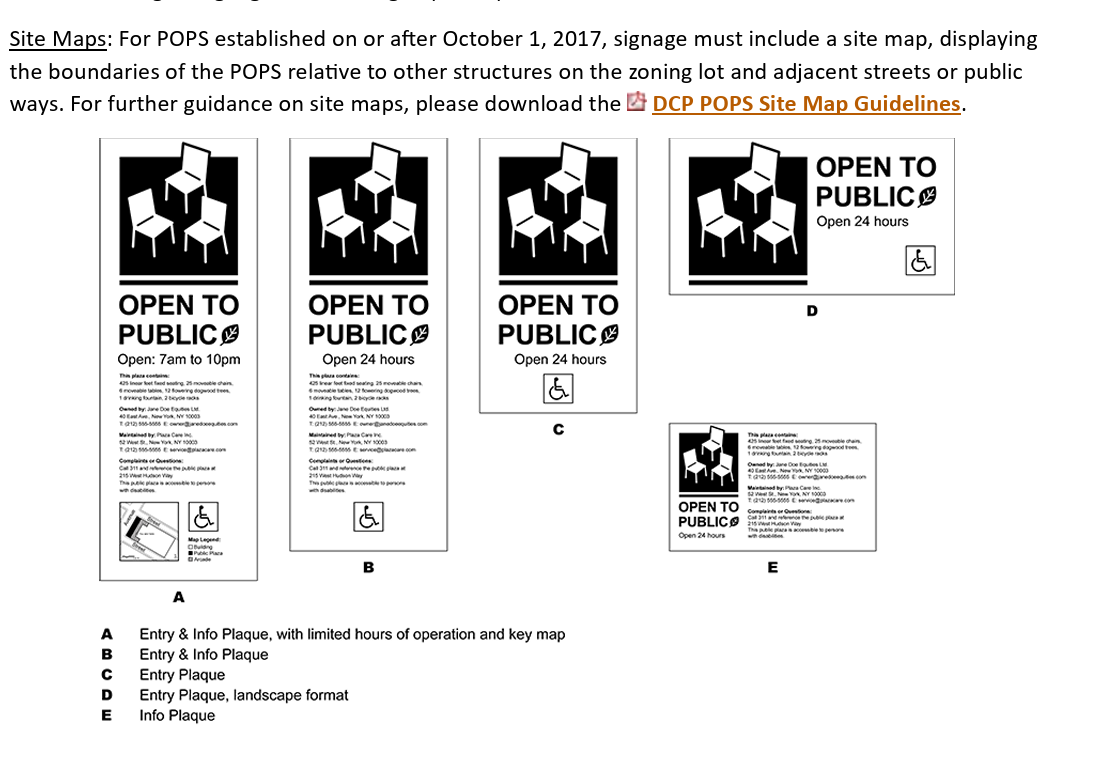

To be considered functional, the city requires POPS to meet certain design and access standards. (For design heads, there’s even a 30 page POPS Standards Book, filled with diagrams and images of what a soothing, functional POPS is supposed to look like. There’s also a FAQs page.)

Violations tend to fall into three broad categories: hostile architecture, restrictive or missing signage, and spaces that are fully or partially closed off. Documented examples include metal spikes added to seating areas, required amenities removed entirely, padlocked gates blocking access, and unauthorized cafés or kiosks privatizing space.

There is relatively little recourse when these violations occur, besides a fine, which, for rich people, is really just a tax: Developers are often willing and able to absorb these costs. In its report, the Times cited a real estate appraiser who estimated that while POPS land across the city is worth roughly $10 billion, building owners had paid just over $1.4 million in penalties at the time of reporting.

Oversight is also inconsistent. The Department of Buildings is supposed to complete an inspection cycle of all POPs every three years; the most recent cycle concluded in 2023, meaning another is technically due this year. In 2017, the New York City Council passed legislation strengthening the City’s oversight of privately owned public spaces, to make them more usable.

Under Local Law 116, later updated by Local Law 250, the Department of City Planning and the Department of Buildings are now required to publish annual reports on POPS and maintain a public, interactive map showing their locations citywide. While some signage requirements have been implemented, inspection and enforcement mostly rely on a complaint-based system. Unless you call 311, no one’s doing much about that inaccessible POPS.

POPS resources & recommendations

POPS may be flawed, inconsistently enforced, and occasionally hostile, but they still make up a huge amount of the city’s usable space. To use a POPS, you gotta know about them. DCP maintains an interactive map of POPS, though I personally don’t find it very user-friendly.

I like this Wikipedia page that lists all of them, for the simple fact that I can learn about them while I use it. I also like this publicly created Google Map I found on the NYC subreddit.

For any data savvy folks, NYC Open Data maintains a database about POPS that’s updated every six months. There’s a ripe market for an app; there was supposed to be one that listed them, but it seems nonfunctional on the app store.

Advocates for Privately Owned Public Spaces (APOPS) also maintains an interactive map. APOPS is a collaborative initiative led by the Municipal Art Society of New York and scholars like Jerold Kayden, who wrote the literal book on POPS. They focus on tracking, mapping and improving POPS in the city. Along with the map, their website provides legal and historical information and tools for the public to rate, comment on and report problems with specific spaces. APOPS’ mission also includes advocacy around POPS so that these spaces live up to the public-use promise.

Other people have discovered the magic of POPS and are getting creative with their usage. FreePOPS is a group that anyone can join, they make public space more participatory while staying within the strict (and sometimes arbitrary and silly) rules of the space they’re in. Past demonstrations include building scaling, drinking milk in public and celebrating Occupy Wall Street’s anniversary. Right now they’re workshopping POPS usage. To sign up, email freepops@lists.riseup.net.

New Topologists is a group of topologists, urbanists, ruralists and artists all concerned with place and cities, that use POPS in their work. Lamp Club, one of the new trendy groups of young, tech-eschewing luddites, also take advantage of POPs. My friend Alex Wolfe is a writer and tour guide who spreads the magic of Midtown through POPS exploration, and a writing class about public space.

Before diving into recommendations, it helps to know a few basics. If you want to use POPs well and push them to be better, know your rights via the standards and FAQ pages.

Know you can (and should) report a POPS violations to 311, like when access is restricted or amenities are missing. Also know, you’re entitled to gather in and use POPS, even if that feels contested in practice. Wolfe's writing class used to meet at 180 Maiden Ln. One of our group was playing the piano, until for no reason at all, a guard told him to stop.

Last summer I threw a publication party in a POPS, complete with snacks, fragrance samples and 50+ people standing around in a circle listening to live readings. The only thing I did in advance was tell security (five minutes before the party started) that it was going to happen. It worked, although I do wonder how they would have reacted if they hadn't been warned.

Of the nearly 590 pops, here’s just a handful of my favorites

Ford Foundation: The Ford Foundation Center for Social Justice feels like a forest in Midtown East. It contains a 12 story indoor atrium filled with trees, vines and nearly 40 species of plants. Visitors can wander among greenery and a reflecting pool under a soaring glass ceiling.

180 Maiden Lane: Near South Street Seaport, this double duty POPS has both indoor and outdoor areas, but most importantly, a publicly available piano to play, one of the few in the city!

550 Madison: This POPS is a huge, plant-filled plaza with mature trees, shrubs and seating. It feels like an urban conservatory. The design blends nature with architectural drama at multiple layers.

Elevated Acre: Up an unmarked escalator in the Financial District, the Elevated Acre is a literal one-acre meadow and garden lifted above the street. With lawns, winding paths, lush plantings and sweeping views of the East River and Brooklyn Bridge, it offers relief from the Financial District’s shadowy streets.

The Winter Garden: Inside Brookfield Place’s soaring glass vaulted pavilion in Lower Manhattan, The Winter Garden sits directly on the Hudson river. It contains giant palm trees, seasonal plantings, and abundant natural light, like a tropical cathedral.

As for what’s next for POPS, Keri Butler, president of the Municipal Art Society, told The Groove that the program is overdue for reconsideration.

"The last major overhaul of the program was in 2007, almost 20 years ago. It’s time to take a fresh look," she said. "Our city has changed, with more dense, mixed-use neighborhoods, a post-COVID hybrid work environment and ever-growing climate change pressures. We need to update the POPS program to ensure these spaces remain accessible, well-maintained, and responsive to the myriad evolving needs of our city’s neighborhoods."

For now the city's nearly 600 POPS in a strange civic hybrid: they're public spaces we’re allowed to use, as long as we know where they are, how they work, and how to insist they live up to what they're supposed to be.

Comments ()