Flush, test, filter up and don't panic

In November, I was one of the New Yorkers blindsided by the news that they’ve possibly been drinking and cooking with lead-tainted water in their home. Gothamist published a map, put together by the New York League of Conservation Voters using data from the Department of Environmental Protection, revealing that around 30% of New York City buildings have (or "possibly have") lead service lines, the underground pipes that deliver water from the water main in the street into your home.

I found my Greenpoint apartment highlighted in red, indicating that its water is serviced by the leaden pipe variety.

I’d lived in my apartment for about a year. Why was this map the first time I was hearing about this? No shade to Gothamist; the map is a public good. But it sort of feels like that’s the kind of information tenants should know, say, before they move into a building. Sure, I already live in a trendy superfund site, but at least I knew that before I moved there. I’d rather not add any more environmental hazards to my day-to-day. What about folks who don’t log on to read the news? Why wasn’t a letter sent out to affected New Yorkers?

I spiraled a little, wondering if I’d been unknowingly poisoning myself with lead all this time. I know a little bit about lead’s effects and that it’s hardest on children, causing developmental problems. In pregnant women, it can be life-threatening for both mom and fetus, increasing the risk of preeclampsia and miscarriage. In non-pregnant adults, the laundry list of possible symptoms ranges from what you might feel on a sub-par day — muscle and joint pain, brain fog — to more clinically-alarming conditions like high blood pressure and reproductive and neurological problems. There’s a statistic that the bones and teeth of adults carry more than 95% of the total lead in the body, which is such a high percentage it almost sounds made up. Once the lead gets in your bones, how does it get out?

After a day of catastrophizing, I calmed down and did some research.

What I found out: The good news is that having lead pipes doesn’t necessarily mean you’ve been exposed to lead in your drinking water. There are simple steps you can take to protect yourself, including testing your water using a free kit from the DEP (more on that below) — but monitoring your lead level, I learned, is an ongoing process, not a one-and-done. You can also flush your water for at least 30 seconds or until it gets cold before drinking and cooking with it, or purchase water filters certified to NSF standards for lead removal.

The bad news? Even with these protective measures to help keep the lead out of your water, the safest bet to eliminate exposure is to remove the lead infrastructure completely, experts told me. A federal rule requires all lead pipes be replaced by 2037, but getting your landlord to act before then isn’t likely.

For now, here are the best steps you can take to educate yourself on and protect yourself from the risk of lead contamination in water.

I’d lived in my apartment for about a year. Why was this map the first time I was hearing about this?

Get your water tested

The DEP provides free water-testing kits (including pre-printed, pre-paid return labels), which you can order online or by calling 311. I had already ordered one of these kits randomly one night during a bout with insomnia, before I even knew I was at risk of lead exposure (I can be very productive during peak neurotic hours!) but hadn’t used it. This turned out to be a lucky move, though; the DEP website currently warns that the agency is receiving a high volume of kit requests. I know ordering was backed up in the weeks after the map came out, and I heard from friends who had to wait a month to even receive a kit.

To test, you take two hefty samples of your tap water, filling large bottles provided in the kit, and mail them in: one, collected immediately after turning on the tap, and another, after flushing the water for 1-2 minutes. Per the directions, make sure you take the samples after not using the faucet for six hours (easier if you do it first thing in the morning or when you get home at the end of the day). If you follow directions you’ll be okay, but there’s a bit more to it than, say, swabbing for Covid.

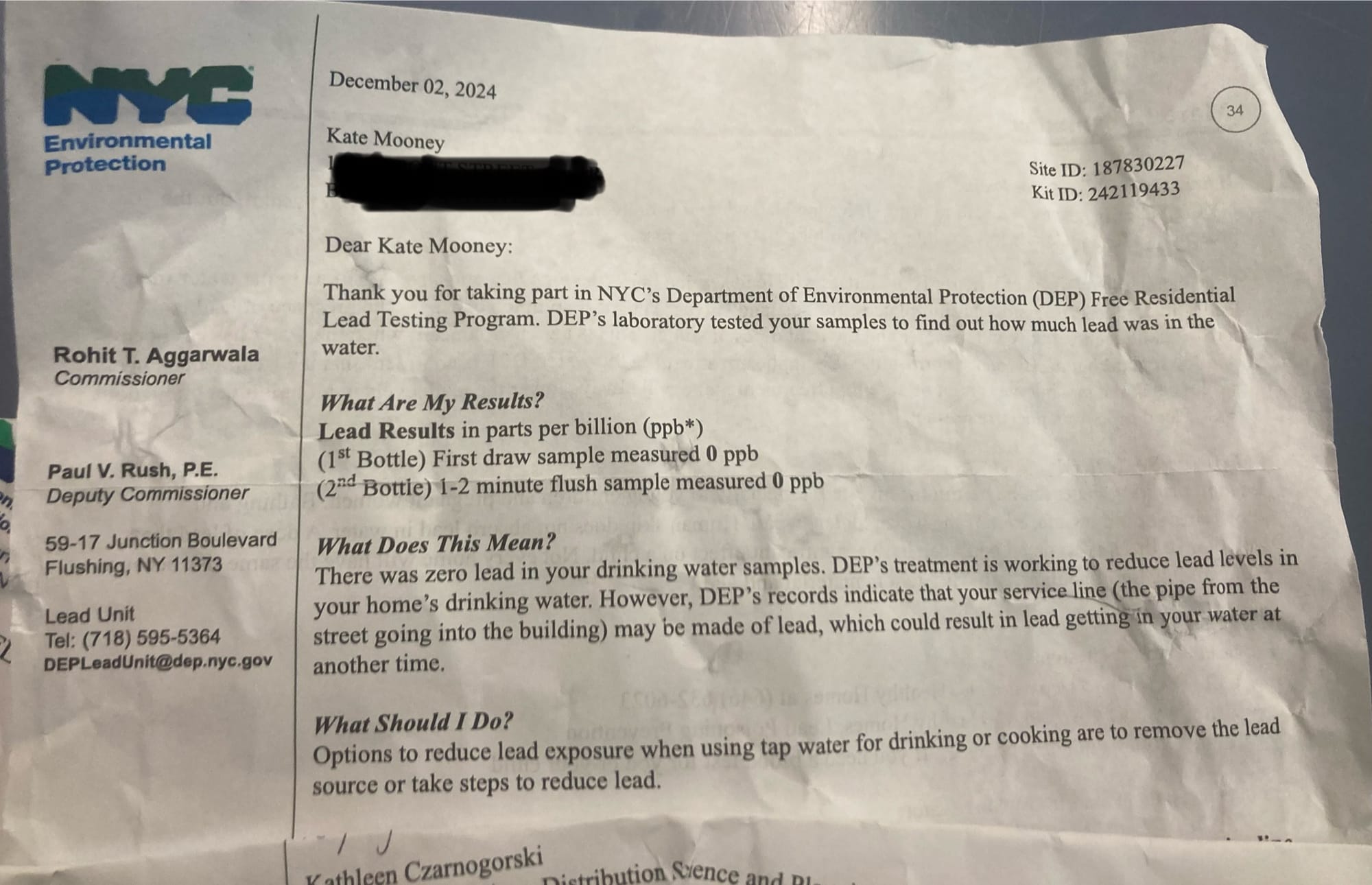

After about three weeks, I received results that 0 parts per billion (ppb) of lead was found in either sample, even though I have a lead water service line. (Hell yeah!) This result is likely because the DEP treats New York City water with orthophosphate, a food-grade additive that helps coat pipes to prevent corrosion, and it’s doing its job.

But that's not the end of it.

“One test does not tell the whole story," said Josh Klainberg, senior vice president for the New York League of Conservation Voters.

Unlike a lead paint chip, which will contain the same amount of lead if you test it over and over again, water results will vary because the conditions are variable. When water is sitting in a lead pipe for long periods of time, lead can leach in, Klainberg explained. And if the pH levels are a little out of whack one day, maybe it’s because the city didn’t add enough orthophosphate, or if there’s a physical disturbance in the street, like construction or a truck going by that causes the pipe to shake, corroding and leaching could occur. But then on another day, the conditions could be smooth sailing for the water.

“We don’t want people to think, oh just do a test once and if you get the reading, that’s it,” Klainberg told The Groove. “You should be testing periodically until that pipe is out, because lead could get in at any point.”

Routinely testing water might not be realistic for New Yorkers, though. Once you mail in your samples, test results can take up to 30 days, and it might take a while to receive the kit to start with. You can order your own, but it will cost you: for example, a Wirecutter roundup of water test kits shows a range from $20 to $500.

Whether you’re waiting for a kit or results to arrive, here are everyday steps to keep yourself safe.

Ways to protect yourself

Flush your water

New York City’s famously great-tasting water, credited with being the secret ingredient to our elite bagels and pizza, is lead-free when it travels from upstate reservoirs down to your street’s water main. It’s only at risk of lead contamination once it gets to your lead water service line and hangs out there for a bit.

But there’s a fix for this: When you turn your tap on for the first time after several hours, like first thing in the morning or when you get home after being gone all day, let the tap run for at least 30 seconds or until it gets noticeably colder. (The drought warning in NYC was officially lifted in early January 2025, so you can feel a little less guilty about doing this.) Then, you know the water you’re drinking is coming from the water main, and not water that’s been stagnating in the service line.

Similarly, only use cold water when you cook—boiling water does nothing to remove lead. If you need to heat the water, always start with flushed cold water first.

Purchase a certified filter

While I was waiting for my test results, I ordered a Brita Elite, which comes with an NSF/ANSI 53-certified filter to remove lead and other contaminants. I still use it daily for all my drinking and cooking needs, both for peace of mind since my water still passes through lead pipes, and because I now prefer the cold filtered taste (sorry NYC tap!).

Look for brands that say NSF/ANSI 53 on the label, which means they’ve been certified according to National Sanitation Foundation and American National Standards Institute safety standards, and are specifically geared to remove lead and other contaminants that cause negative health effects, like mercury, PFOA and PFOS. (Check that lead is specifically mentioned on the label; other NSF/ANSI standards serve different purposes like removing chlorine and water softening. While researching this piece, I found that my Brita Elite wasn’t mentioned on the NSF list of filters that are certified to remove lead, despite claims on Brita’s website. I reached out to NSF and will update the story when they respond.

[UPDATE 2/12: I learned that a number of independent testing organizations can certify products to NSF/ANSI standards, including the Water Quality Association (WQA), UL Solutions (formerly Underwriters Laboratories), CSA Group (Canadian Standards Association), and the NSF. A rep from the WQA confirmed that my Brita Ultramax Water Dispenser paired with the Brita Elite filter is in fact certified to NSF/ANSI 53 for lead removal by the WQA.]

You can go with a pitcher, a faucet-mounted filter, or an under-the-sink attachment to your pipes. Learn more about NSF certification here. And remember to update your filter every six months or as indicated to ensure it’s continuing to do its job.

Representative Richie Torres on Wednesday introduced a bill that would give a 20% tax credit to homeowners and renters for purchase of water-filtration systems that remove lead. Which, if it passes, is something.

Clean your faucet aerator

Over time, the screen on your sink faucet can get clogged and trap lead particles, so it’s a good idea to clean it every so often. Remove it, scrub it, and soak it in vinegar, then reattach. Here’s a guide on how to do it.

What about getting your lead pipes replaced?

In 1961, the city banned the use of lead in water service lines. If your building was built before 1961 and no one’s replaced the service line since then, you might be at risk. And until as recently as 1987, household plumbing, including fixtures, pipes and solder, could legally be constructed using lead materials. So even if your water service line is lead-free, there could be problem areas within your home.

In October 2024, President Biden passed The Lead and Copper Rules Improvements, a federal EPA rule requiring water utility companies nationwide to identify and replace all lead pipes within 10 years, starting in 2027, giving them time to plan repairs. The EPA estimates 9 million lead pipes need to be replaced, at a cost of $45 billion over the decade, and so far there’s about $17.5 billion in federal funding to help out. But the big question on a local level is: who will pay for the difference?

While the laws vary across the nation, water service lines are the responsibility of homeowners in New York City. The law does not require water utility companies to replace privately owned lines. So, if you rent in NYC, it will likely fall on your landlord to replace the pipes, which could cost between $5,000 and $10,000 per service line. There’s currently no legal requirement for that to happen before the 2037 deadline. And when it does happen, some are worried the financial cost will be passed onto renters, or that homeowners in disadvantaged communities, where there’s a higher concentration of lead service lines, will be disproportionately affected.

In July of 2024, the NYC DEP launched a pilot program that awards up to $10,000 to Bronx homeowners to cover the cost of replacing their lead service lines. Homeowners can’t apply for the funding, but instead are contacted directly by the DEP.

Call your reps

Klainberg suggested New Yorkers contact their City Council member about the possibility of a city-run program that would assume the costs and replacement of lead pipes. And for anyone worried about potential challenges to the Lead and Copper Rules Improvements under the Trump administration, which might come via federal funding cuts to the EPA? Contact your representative to tell them not to roll it back.

Rob Hayes, director of clean water for Environmental Advocates of New York, told New York Focus that New York could replace lead pipes sooner than the 2037 deadline, if it made it a priority. He cited Newark, New Jersey as an example, where the city replaced 23,000 lead pipes in under three years.

What about medical testing?

Say your water test comes back positive for lead, and you’re wondering how the levels are in your blood—whether you have symptoms or not. The first step is a blood lead test, Morri Markowitz, Director of the Lead Poisoning Prevention and Treatment Program at the Children's Hospital at Montefiore, told The Groove. You can talk to your primary care doctor, or order one from Quest Diagnostics.

But just like a lead water test, a blood lead test isn’t the final word on lead levels in your body, but rather a snapshot taken at a single time point. Additional and routine testing may be needed.

“If the lead level in your blood is extremely low, close to zero [micrograms per deciliter], then it’s unlikely that you’re having an ongoing ingestion and absorption of lead,” Markowitz explained. “But, it doesn’t mean you don’t have lead in your body.”

At high levels of lead in the blood, chelation therapy, a medicine that binds to metals in the body and induces lead removal through urine, can be effective. For low to medium levels, Markowitz said specialists direct patients towards prevention, like removing the source of lead exposure; proper nutrition via a diet rich in Vitamin C, iron and calcium, which can lower lead absorption in the body; and behavioral modifications, like flushing the tap water and only using cold water to make baby formula, or properly cleaning lead paint chips or dust kicked up from construction.

In New York City, pregnant women are required to be tested for lead at their first doctor’s visit, and children are tested at age one and age two.

Greater outreach and resources are needed to protect New Yorkers from lead exposure before medical consequences set in. Hopefully elected officials will prioritize replacing our lead pipes so that we don’t have to wait more than a decade to drink safe water. But until we get the lead out the right way, through removing lead infrastructure, getting the word out about the risk, and taking steps to protect yourself, is our best bet.

Comments ()